×

Transcript

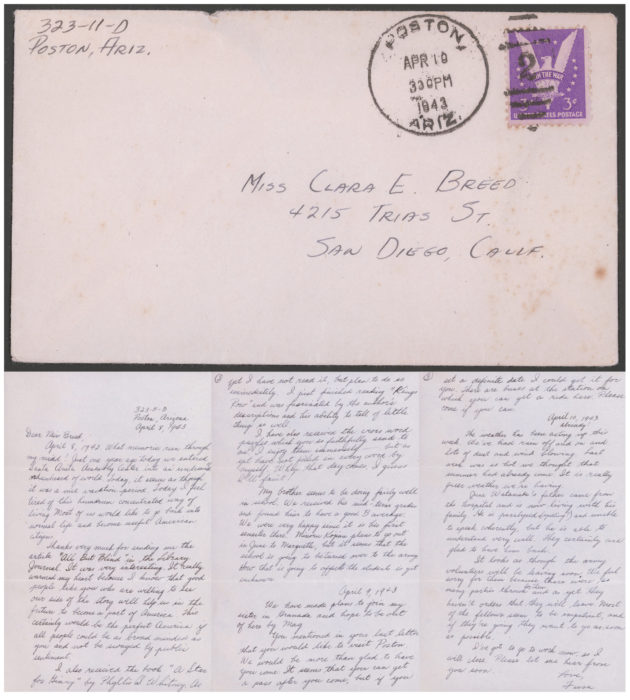

323-11-D

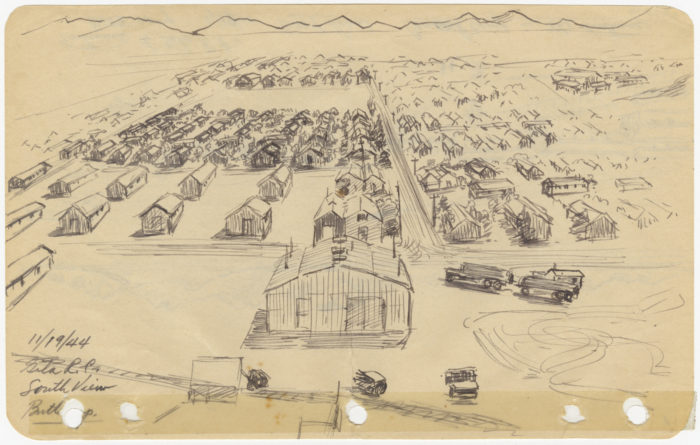

Poston, Arizona*

April 8, 1943

Dear Miss Breed,

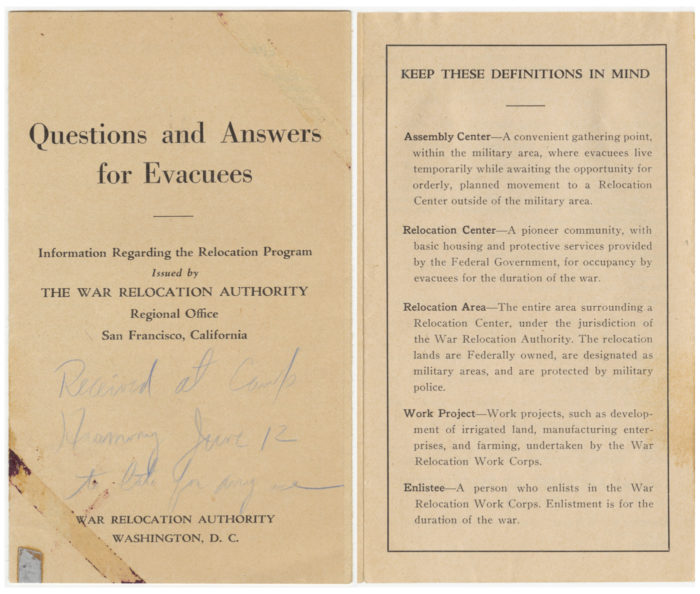

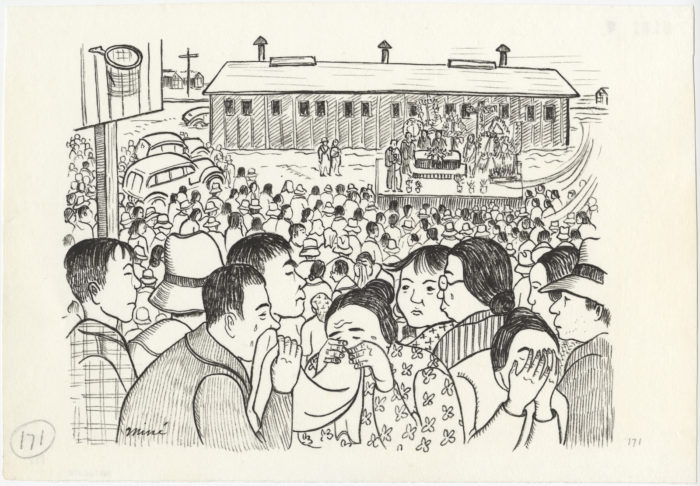

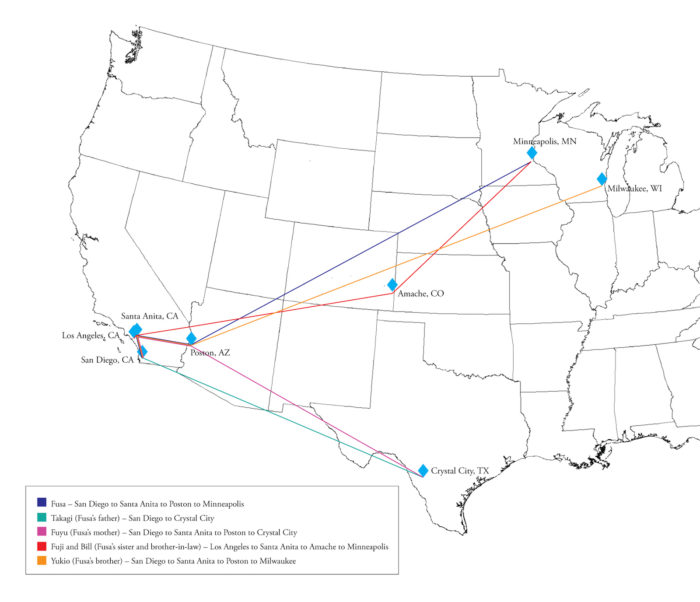

April 8, 1942. What memories run through my mind! Just one year ago today we entered Santa Anita Assembly Center† into an undreamed of and unheard of world. Today, it seems as though it was a nice vacation period. Today I feel tired of this humdrum concentrated way of living. Most of us would like to go back into normal life and become useful American citizens.

Thanks very much for sending me the article “All But Blind” in the Library Journal. It was very interesting. It really warmed my heart because I know that good people like you who are willing to see our side of the story will help us in the future to become a part of America. This certainly would be the perfect America if all people could be as broad minded as you and not be swayed by public sentiment.

I also received the book “A Star for Ginny” by Phyllis A. Whitney. As yet I have not read it, but plan to do so immediately. I just finished reading “Kings Row” and was fascinated by the author’s descriptions and his ability to tell of little things so well.

I have also received the cross word [sic] puzzles which you so faithfully send to me. I enjoy them immensely—but as yet have not filled in every word by myself. When that day comes, I guess I’ll faint!

My brother seems to be doing fairly well in school. We received his mid-term grades and found him to have a good B average. We were very happy since it is his first semester there. Minoru Kojima plans to go out in June to Marquette‡, but it seems that the school is going to be turned over to the army. How that is going to affect the students is yet unknown.

April 9, 1943

We have made plans to join my sister in Granada§ and hope to be out of here by May.

You mentioned in your last letter that you would like to visit Poston. We would be more than glad to have you come. It seems that you can get a pass after you come, but if you set a definite date I could get it for you. There are buses at the station on which you can get a ride here. Please come if you can.

April 10, 1943

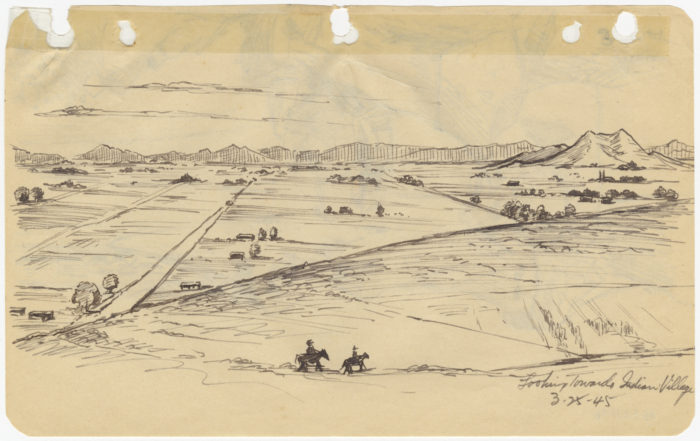

The weather here has been acting up this week. We’ve had rain off and on and lots of dust and wind blowing. Last week was so hot we thought that summer had already come. It is really queer weather we’re having.

June Watanabe’s father came from the hospital and is now living with his family. He is paralysed (spelling?) and unable to speak coherently, but he is able to understand very well. They certainly are glad to have him back.

It looks as though the army volunteers will be leaving soon. We feel sorry for them because there were so many parties thrown for them and as yet they haven’t orders that they will leave. Most of the fellows seem to be impatient, and if they’re going they want to go as soon as possible.

I’ve got to go to work now, so I will close. Please let me hear from you soon.

Love,

Fusa

* Poston is a concentration camp located in Arizona.

† Santa Anita is in Santa Anita, California

‡ Marquette is a university in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

§ Granada is a concentration camp located in Colorado.