Overview Essay

The World War II Japanese American Social Disaster: A Brief Overview

Japanese American National Museum (2015.100.367a) Click to open full-size image in new tab.

Following Japan’s attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base in the American territory of Hawai‘i* on December 7, 1941, the US government removed more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from their homes and communities on the West Coast and beyond, confining them in American-style concentration camps. The government’s rationale for this enforced mass uprooting and migration of Japanese Americans was military necessity and national security. For the duration of the war, the Japanese Americans were consigned to remote and crude detention facilities located in the interior of the country, in windblown desert and boggy forestland. They lived in rickety, unfurnished barracks apartments in communities guarded by armed sentry and encircled in barbed wire.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Walter Muramoto Family (97.292.13Q) Click to open full-size image in new tab.

Roughly two-thirds of these imprisoned Japanese Americans were native-born Americans (Nisei), all of whom possessed US citizenship. These were the children of immigrants from Japan (Issei) who largely settled in Hawai‘i and the US mainland between 1880 and 1924 yet were banned by law from becoming naturalized citizens. The Nisei were 17-to-18 years old on average and were usually single. Most of the Nisei were educated in the United States but a few—known as Kibei-Nisei, or simply Kibei—were educated and socialized in Japan. A great number of Nisei and Kibei, despite being stripped of many of their civil rights, served in the wartime ranks of the US military with patriotic pride and high distinction. A relatively small number of older Nisei and Kibei, some of whom achieved leadership positions along with the Issei in the inmate population, were married; some were even the parents of third-generation children (Sansei).

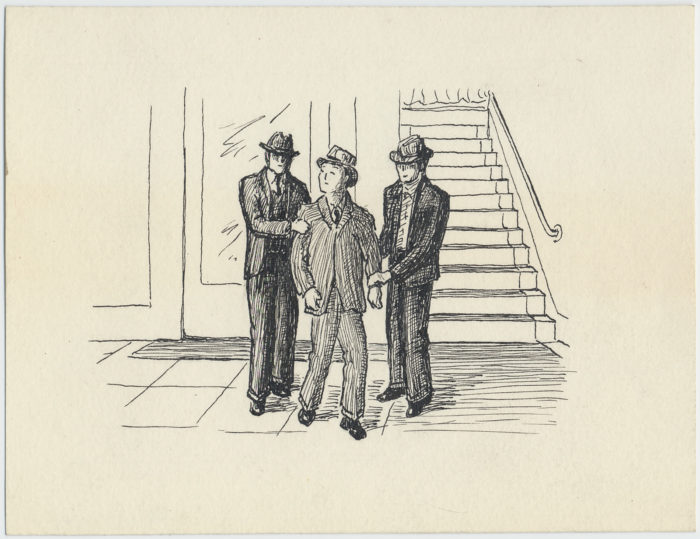

Estelle Ishigo, Untitled, c. 1942–45, ink on paper, Japanese American National Museum (94.195.7O) Click to open full-size image in new tab.

One important result of the declaration of war between Japan and the United States was the separate incarceration of some 7,000 law-abiding Issei―Japanese American community leaders and others who were identified by federal intelligence units and deemed “potentially dangerous”―in alien-enemy internment camps managed by the US Department of Justice.

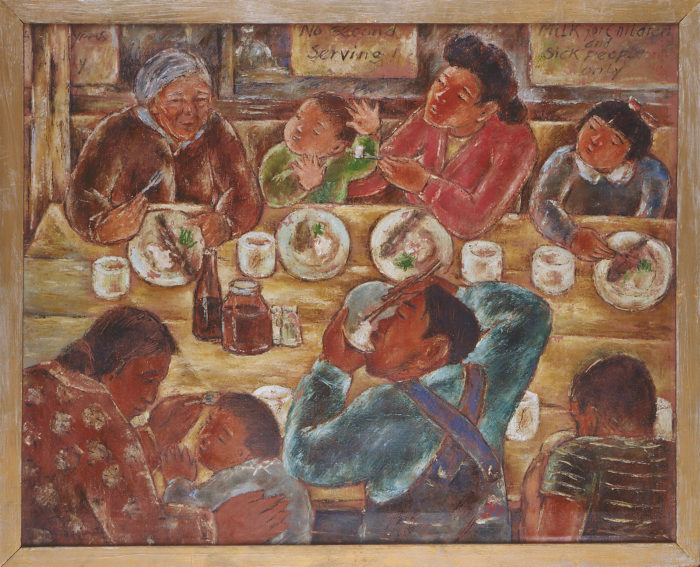

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Our Mess Hall), 1942, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.56) Click to open full-size image in new tab.

By contrast, the 10 permanent detention camps administered by the War Relocation Authority lacked any legal basis for their operation. The inmates of these comparatively humane compounds, while not subjected to the grisly horrors facing Jews and other tormented groups in the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, were unquestionably victimized daily by privations and indignities, and faced the very real possibility of being shot by trigger-happy military police. While most inmates did not actively resist their treatment by the guards, some, such as loyal and principled draft resisters, challenged the constitutionality of their incarceration through mass protests, violent and non-violent, against various government policies.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Jack and Peggy Iwata (93.102.8) Click to open full-size image in new tab.

Until recently, the World War II experience of Japanese Americans was widely referred to as an “evacuation.” More recently it has been characterized as incarceration. Perhaps, though, it should be known as a social disaster. Unlike natural disasters, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and fires, the disaster that befell the Japanese Americans was not the result of physical or natural causes but human-made ones: racism, exploitation, improper government leadership, and lack of public vigil. What happened to Japanese Americans during World War II should never have occurred. That it did, however, has one saving grace: it provides Americans with a negative object lesson, one that must be carefully and conscientiously studied so we can protect our constitutional democracy and take the necessary steps to prevent such social disasters from ever happening to any group of people again.

* Hawaiʻi did not become a state until 1959.