Manzanar

Location: Manzanar, Calif.

Peak population: 10,046

Date opened: June 2, 1942

Date closed: November 21, 1945

Over 90 percent of the people held at Manzanar were from the Los Angeles area; others were from Stockton, California, and Bainbridge Island, Washington.

Located at 3,900 feet of desert elevation in the southern Owens Valley of east-central California, between the towns of Lone Pine and Independence, Manzanar was 220 miles north of Los Angeles and 250 miles south of Reno, Nevada. Its 6,000 acres were framed by the Sierra Nevada mountains to the west and the White-Inyo mountain range to the east. Summers were hot and winters cold, with an annual rainfall under six inches although the area has rivers fed from mountain runoff. The vegetation was mostly sagebrush.

Of special interest is the Manzanar Riot, which took place on December 5–6, 1942. Manzanar was the only camp to have an orphanage for Japanese American children.

For more info about Manzanar, click here.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

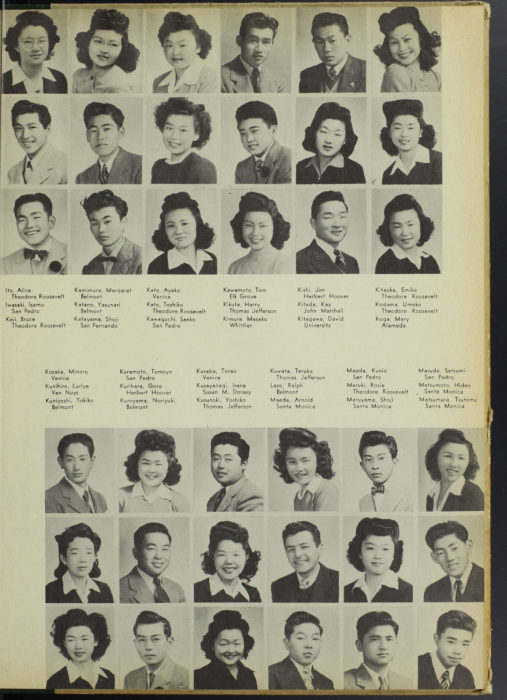

This is a page from the 1944 Manzanar High School yearbook. Look carefully at these faces and names.

- What do you notice?

As one might expect, almost all of the students pictured in the yearbook are Japanese American. There is one student, however, who is not. Find the photograph of Ralph Lazo. Lazo is of Mexican and Irish descent.

- Why do you think he is pictured in this yearbook from Manzanar Concentration Camp?

- What events might have led to him living in Manzanar?

“Public Proclamation No. 29” (April 30, 1942), Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.13)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

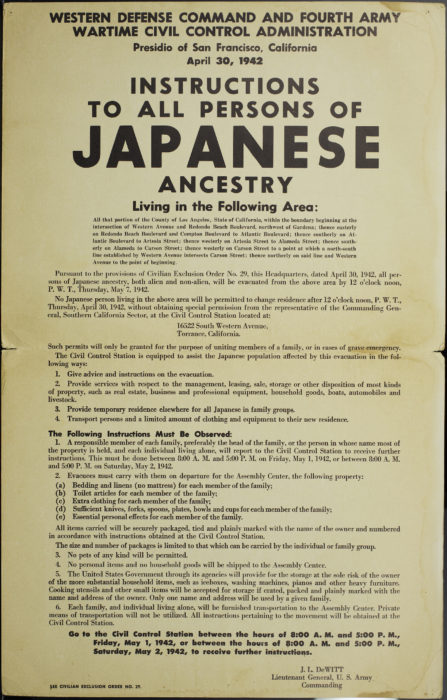

Read the text of this document carefully. This is a Civilian Exclusion Order. In 1942, these posters were placed in public areas all along the West Coast of the United States.

- To whom are these instructions directed?

- If you were a person of Japanese ancestry, how would you feel as you read these posters?

- If your best friend was a person of Japanese ancestry, how would you feel as you read these posters?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

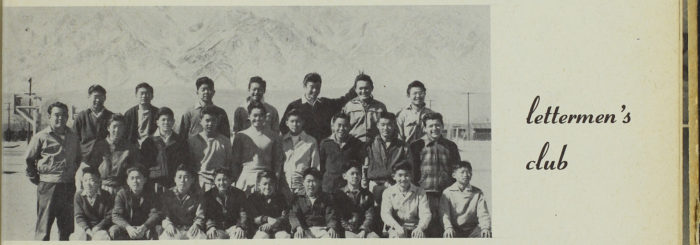

Although Ralph Lazo was not Japanese American, many of his friends at Belmont High School in Los Angeles were. When the Civilian Exclusion Order called for all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast to be incarcerated in concentration camps, Ralph witnessed many of his good friends forcibly removed from their homes and sent to camp. He considered his Japanese American friends to be his equals. Realizing the incarceration was unjust and wishing to support his friends, Ralph decided he would go to camp as well. He ended up living at Manzanar and going to high school there.

Take a look at this photograph from the Manzanar High School yearbook.

- Can you find Ralph Lazo?

- Does he stand out from the others in a drastic way?

- How would you describe his mood?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Hannah Tomiko Holmes (94.181.134)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

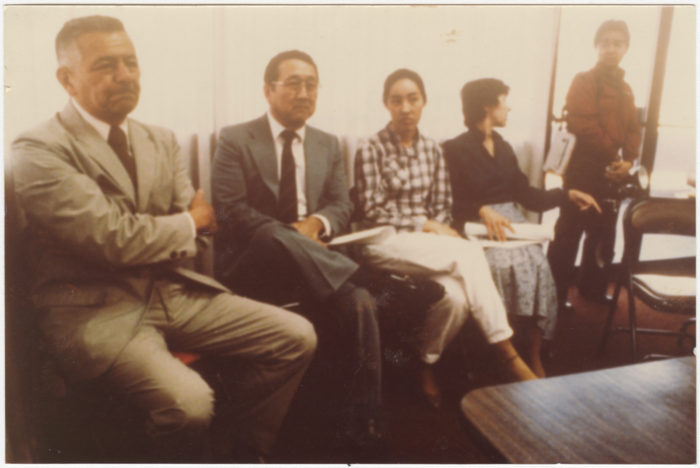

This snapshot was taken during a press conference for the National Council for Japanese American Redress, many years after the teenaged Ralph Lazo joined his friends at Manzanar. The council was formed in 1979 to obtain restitution for Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II. In this photograph, Lazo is shown on the left.

- By looking at this photograph taken decades after World War II, what do you learn about Ralph Lazo as an adult?

Lazo’s presence in this photograph shows how even decades after World War II he continued to support his Japanese American friends and the Japanese American community.

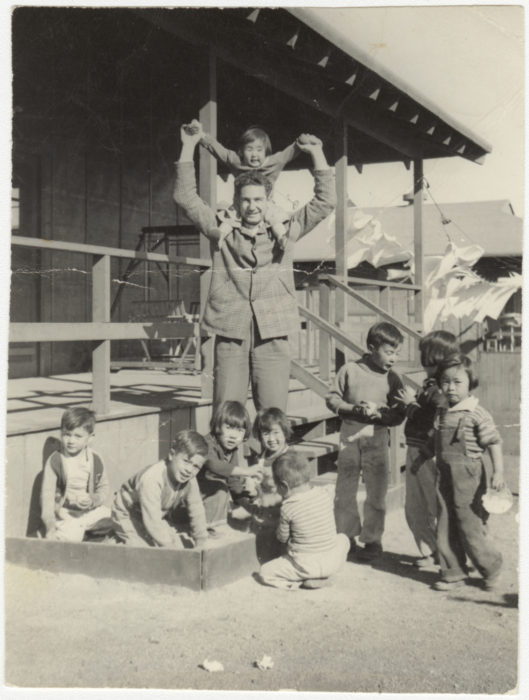

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Charles and Lois Ferguson (94.180.7)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Orphans, which is about Identity.

Look closely at this image.

- How would you describe what is happening?

- Where might this picture have been taken?

- How would you describe the children in this picture?

- About how old are they?

- How would you describe the expressions on their faces?

- How would you describe the adult in this picture?

- Who do you think he might be?

- What other questions arise when you examine this image?

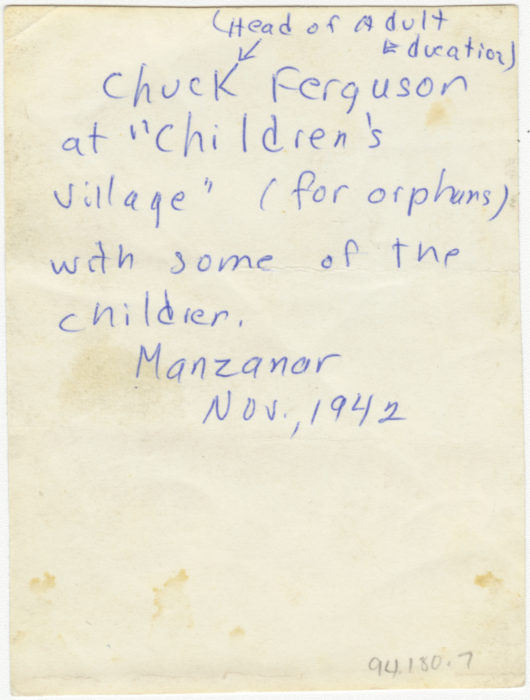

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Charles and Lois Ferguson (94.180.7)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Orphans, which is about Identity.

This is written on the back of the photograph you just saw.

- What is the name of the man in the photo?

- What was he in charge of?

- What do you think the “Children’s Village” was?

- Who are the children in the picture?

At the time World War II broke out, there were three orphanages within California to care for children of Japanese descent (including mixed-race Japanese children) and to serve the needs of the Japanese American community. Two of these orphanages, the Shonien and the Maryknoll Catholic Home, were in Los Angeles; the Salvation Army Children’s Home was in San Francisco.

The children in these orphanages were there for various reasons. Sometimes their parents died or were too ill to care for the children because of mental illness or contagious diseases like tuberculosis. Other children were there temporarily while their parents could get back on their feet again financially.

When the Japanese Americans were removed from the West Coast, Japanese American children in these three orphanages were removed and placed in the Manzanar Children’s Village. The children ranged in age from infants and toddlers to 18-year-olds, and their experiences at Manzanar varied greatly. Nearly 20 percent of the Japanese American children were of mixed race.

Lillian Matsumoto, from “Memories of the Children’s Village at Manzanar,” public program, January 14, 2007, Japanese American National Museum

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Orphans, which is about Identity.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) appointed Harry and Lillian Matsumoto, husband and wife, as superintendent and assistant superintendent of the Manzanar Children’s Village. Before departing for Manzanar, the Matsumotos had worked at the Shonien, a Japanese American children’s home in Los Angeles, alongside the Shonien’s founder, Rokuichi Kusumoto. The State of California Department of Welfare recommended to the WRA that the Matsumotos, who had graduate-level education in business (Harry) and social welfare (Lillian), be placed in charge of the children at camp.

In this video clip, Lillian Matsumoto remembers taking the bus to Manzanar with the orphans. Watch the clip to hear her tell you which song one of the girls sang.

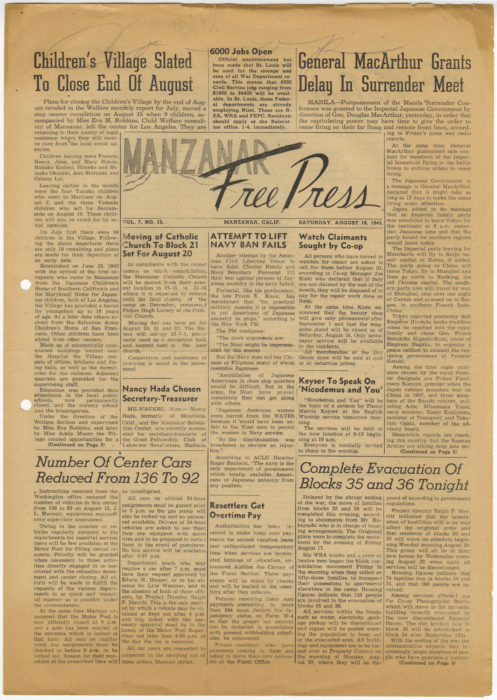

Manzanar Free Press (August 18, 1945), Japanese American National Museum, Gift in Memory of Joe H. Kishi (99.107.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Orphans, which is about Identity.

According to the War Relocation Authority’s final accountability roster on the Children’s Village, approximately half of the 101 orphans were reunited with one or both parents, and “nearly 25% were divided among institutions and wage homes. Only a few were adopted or placed in foster homes.”*