Jerome

Location: Denson, Ark.

Peak population: 8,497

Date opened: October 6, 1942

Date closed: June 30, 1944

Jerome held people from Los Angeles, Fresno, and Sacramento, California. Many Japanese Americans from Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, were also sent to Jerome and lived alongside the mainland Japanese American population, reflecting the diversity of the Japanese American community.

Jerome was located in the Mississippi River Delta region 12 miles west of the Mississippi River, 18 miles south of McGehee, and 120 miles southeast of Little Rock. The 10,000-acre area was impoverished and consisted of heavily wooded swampland. It was 27 miles south of the Rohwer concentration camp. Summers were hot and humid, with chiggers, mosquitoes, and poisonous snakes.

The Jerome War Relocation Center was the first camp to close, on June 30, 1944.

For more info about Jerome, click here.

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

Look closely at this image.

- What do you observe?

- What is depicted?

Consider clothing, background, mood, composition, and color.

- Who might this person be?

- What makes you say that?

- What is the setting for this image?

- What makes you say that?

- What does the writing in the lower left corner say?

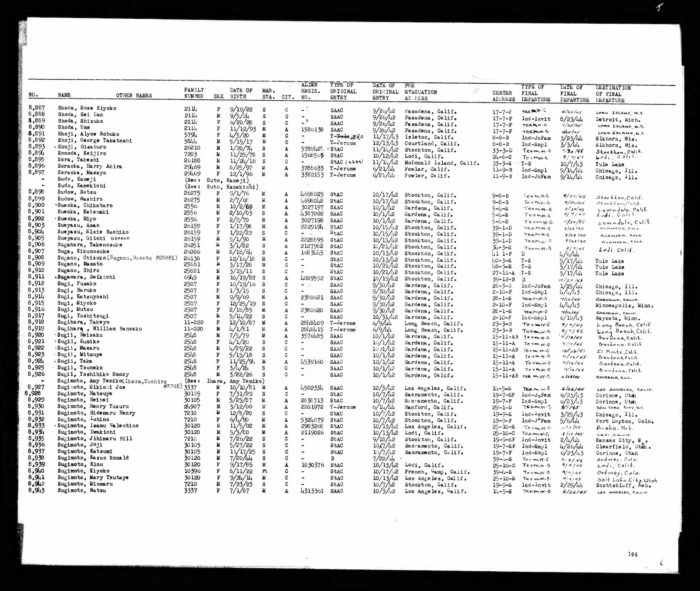

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

- Does this historical document give you a better sense of who H. Sugimoto is?

- What new evidence do you have about him?

- Where did he live before World War II?

- Where did he go after World War II?

Henry Sugimoto, quoted in Kristine Kim, Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 55.

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

- What does this quotation by Sugimoto say about him?

Japanese Americans could not bring cameras of any kind into the camps, preventing the documentation of their treatment and living conditions; even artistic representation of life in the camps was considered suspect. Still, the moment of his arrival at Fresno, Henry Sugimoto resumed sketching and painting despite his worries about surveillance and arrest. Mr. Sugimoto’s anxiety was outweighed by the sense of purpose he found: his skill as an artist made it possible for him to record, for history, the experiences of Japanese Americans in the camps. As he remarked later in life:

“I depicted camp life . . . with an artist’s sense of mission.”

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1982, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.99)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

Look closely at this image, also a self-portrait by Henry Sugimoto. This was painted in 1982, almost forty years after the other self-portrait.

- What do you observe?

- Do you see the medals in this portrait?

Mr. Sugimoto was awarded many honors during his life, including the medals shown here.

- Why do you think he included the medals in this portrait?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

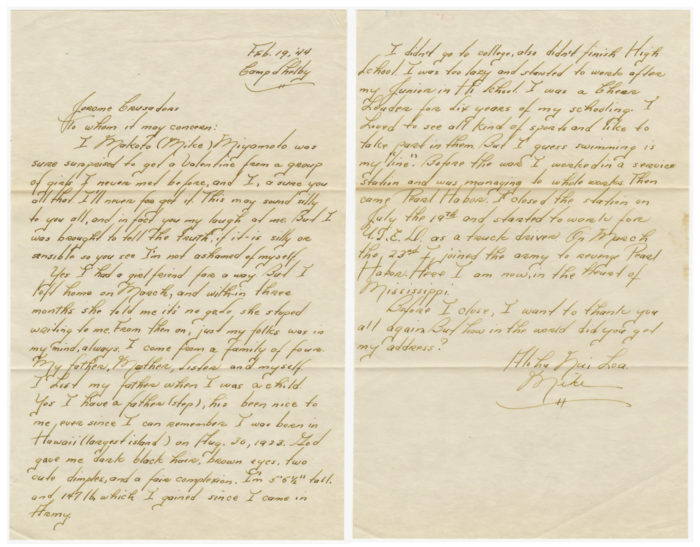

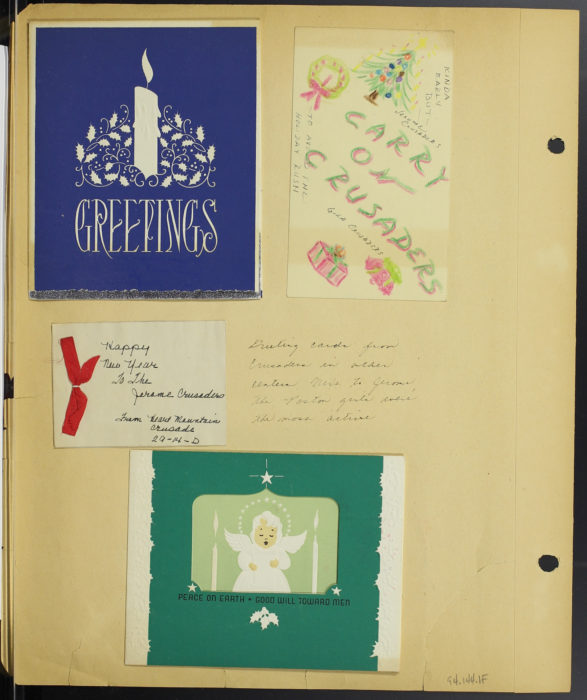

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

Take a look at this letter from 1944.

- To whom is it addressed?

- Who sent it?

- What type of information is being shared?

- Do you think the writer knows the recipients?

While incarcerated in Jerome, Arkansas, a small group of five Sunday school students and their teacher, Mary Nakahara (who later became notable civil-rights activist Yuri Kochiyama), decided to start writing to Japanese Americans serving in the military. This effort grew as other students and parents joined in. They wrote to soldiers whose names they gathered by asking around in their community to find those with family members serving in the military. The letter-writers called themselves the Crusaders.

This page is taken from a scrapbook of letters and cards exchanged between the soldiers and the Crusaders. It was compiled and saved by Rinko Shimasaki, one of the high school students who corresponded with the soldiers.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

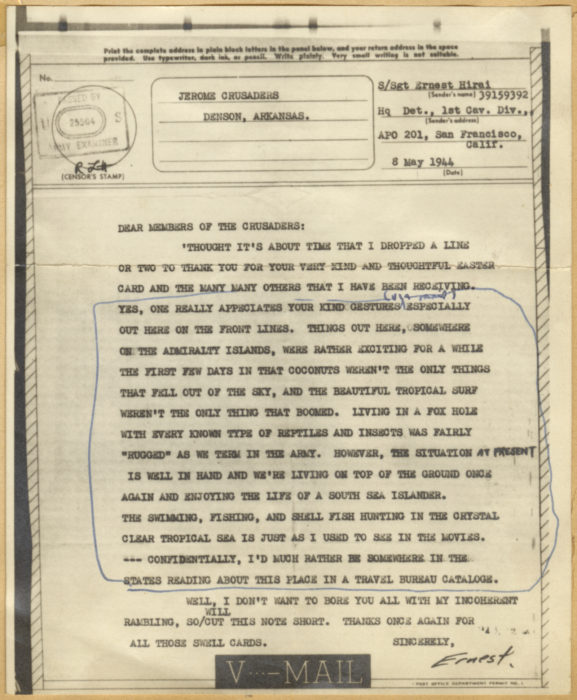

This is a letter to the Jerome Crusaders from Sgt. Ernest Hirai.

- What is the tone of this letter?

- By reading this letter, what can you gather about the conditions in which Sgt. Hirai is living?

- Look at the designs on the paper on which the letter is typed. What details do you notice?

- Do you see the censor’s stamp? Why would this letter need to be censored?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (96.144.1F)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

This is a page from the Crusaders’ scrapbook. Look closely at these greetings.

- To whom are they addressed?

- Who sent them?

The Crusaders expanded beyond Jerome with members in other camps as well.

- What evidence of membership in other camps can you see on this page of greeting cards?

The Crusaders were a strong network of letter writers. Despite the distance between the camps, the Crusaders shared a desire to support the soldiers in their communities and show they cared.

Yuri Kochiyama video interview (June 16, 2003), Japanese American National Museum, DiscoverNikkei.org

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

In this video clip, Yuri Kochiyama talks about how a project started by a small group of young students grew rapidly to include many.

- What do you think compelled so many people to become involved?