Through an Artist’s Eyes

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look closely at this image.

- What do you observe?

- What is depicted?

Consider clothing, background, mood, composition, and color.

- Who might this person be?

- What makes you say that?

- What is the setting for this image?

- What makes you say that?

- What does the writing in the lower left corner say?

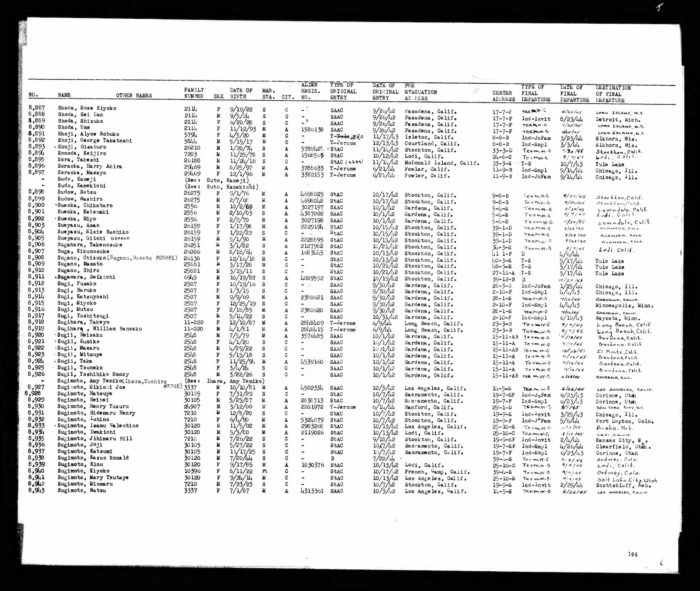

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- Does this historical document give you a better sense of who H. Sugimoto is?

- What new evidence do you have about him?

- Where did he live before World War II?

- Where did he go after World War II?

Henry Sugimoto, quoted in Kristine Kim, Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 55.

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What does this quotation by Sugimoto say about him?

Japanese Americans could not bring cameras of any kind into the camps, preventing the documentation of their treatment and living conditions; even artistic representation of life in the camps was considered suspect. Still, the moment of his arrival at Fresno, Henry Sugimoto resumed sketching and painting despite his worries about surveillance and arrest. Mr. Sugimoto’s anxiety was outweighed by the sense of purpose he found: his skill as an artist made it possible for him to record, for history, the experiences of Japanese Americans in the camps. As he remarked later in life:

“I depicted camp life . . . with an artist’s sense of mission.”

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1982, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.99)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look closely at this image, also a self-portrait by Henry Sugimoto. This was painted in 1982, almost forty years after the other self-portrait.

- What do you observe?

- Do you see the medals in this portrait?

Mr. Sugimoto was awarded many honors during his life, including the medals shown here.

- Why do you think he included the medals in this portrait?

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.5); Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1982, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.99)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- In what ways are these two images similar?

- In what ways are they different?

- Would you say that a sense of dignity is conveyed in these self-portraits? If so, how?

The portrait of the artist in the beret is Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp). It was painted by Mr. Sugimoto in 1943 while he was incarcerated in Arkansas, and it makes a profound statement about his determination to continue as an artist during this period.

Everything in the painting—palette, easel, canvases, beret—proclaims his identity as an artist. The context of the camp, so undeniably stated in almost all of his other paintings from this period, is notably absent here. Sugimoto instead paints himself in an artist’s studio, surrounded by the paintings he is most proud of—his body of work from time spent in France. In this, his only wartime self-portrait, Sugimoto presents himself not as an incarcerated man but as a serious artist.

—Kristine Kim, Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 83.

Additionally, Mr. Sugimoto made his identity known throughout the camp by hanging a palette-shaped sign above the door to his barracks with the title “Artist” painted on it.

There was a sense of enthusiasm and purpose to his work, which spanned most of the twentieth century. To see him, frail yet energized, standing before the easel with palette in hand, applying sure brushstrokes to canvas, is a cherished image. My father, even in his last years, told me that to be able to paint “even for fifteen minutes makes me feel alive.”

—Madeleine Sugimoto, daughter of Henry Sugimoto

Return to Dignity