Camp

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.5)

This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

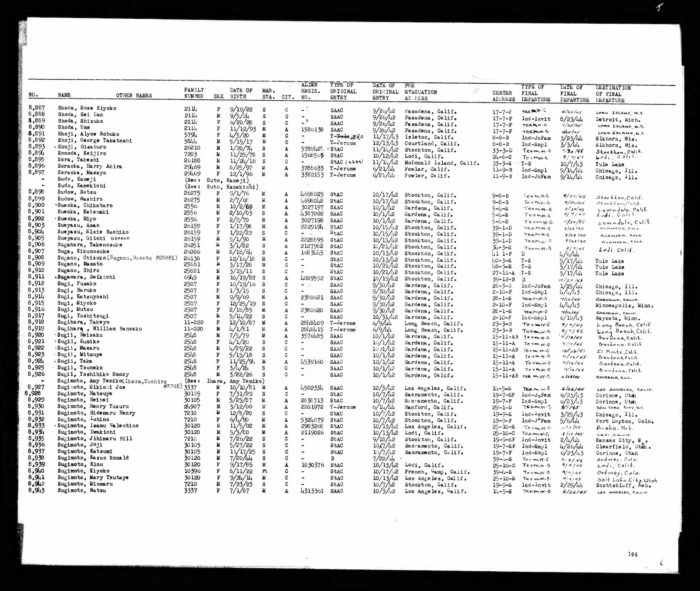

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

Henry Sugimoto, quoted in Kristine Kim, Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 55.

This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

- What does this quotation by Sugimoto say about him?

Japanese Americans could not bring cameras of any kind into the camps, preventing the documentation of their treatment and living conditions; even artistic representation of life in the camps was considered suspect. Still, the moment of his arrival at Fresno, Henry Sugimoto resumed sketching and painting despite his worries about surveillance and arrest. Mr. Sugimoto’s anxiety was outweighed by the sense of purpose he found: his skill as an artist made it possible for him to record, for history, the experiences of Japanese Americans in the camps. As he remarked later in life:

“I depicted camp life . . . with an artist’s sense of mission.”

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1982, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.99)

This object is part of the story Through an Artist's Eyes, which is about Dignity.

Look closely at this image, also a self-portrait by Henry Sugimoto. This was painted in 1982, almost forty years after the other self-portrait.

- What do you observe?

- Do you see the medals in this portrait?

Mr. Sugimoto was awarded many honors during his life, including the medals shown here.

- Why do you think he included the medals in this portrait?

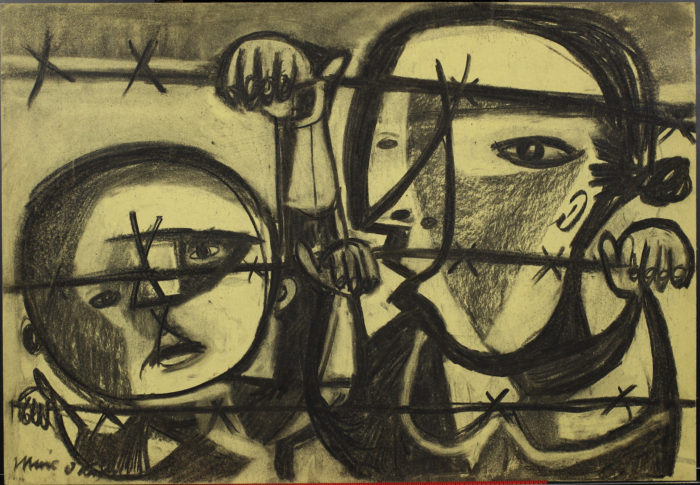

Miné Okubo, Untitled, n.d., charcoal on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.5)

This object is part of the story Sketches from Within, which is about Justice & Democracy.

- What do you see depicted in this charcoal drawing by Miné Okubo?

- Based on body language and facial expressions, what can you infer about these figures?

- What emotions are evoked by this drawing?

Miné Okubo is a Japanese American artist best known for her black and white ink drawings, though this sketch is done in charcoal. As you view more of her works on this website, consider how her artistic tools change the mood of her drawings and why she may have chosen to do this particular scene in charcoal rather than ink.

- How is this sketch different from or similar to the rest of her work?

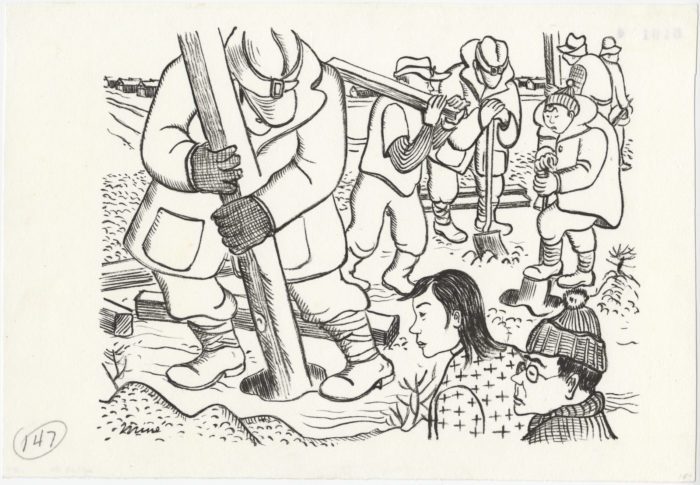

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Fence and watchtower construction, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.154)

This object is part of the story Sketches from Within, which is about Justice & Democracy.

This is a drawing of the Topaz concentration camp by Miné Okubo. She documented her personal story as a Topaz inmate in great detail through her drawings and paintings. Many of her drawings were published in an autobiographical book titled Citizen 13660. In this book, Okubo provided descriptions to accompany each image. Here’s what she wrote about this image:

Fence posts and watch towers were now constructed around the camp by the evacuees to fence themselves in.

- What thoughts do you have as you read this description?

- What questions do you have?

- How does this image heighten the sense of injustice in incarcerating people without cause?

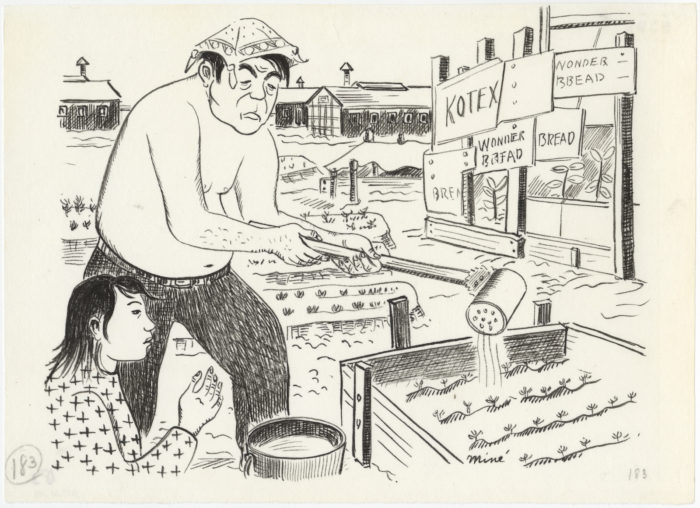

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Victory gardens, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2000.62.190)

This object is part of the story Sketches from Within, which is about Justice & Democracy.

This is another drawing by Miné Okubo that depicts life at Topaz.

- What do you think the individuals in this drawing are doing?

- Where are they?

- Can you tell what the climate there is like by looking at this drawing?

In Citizen 13660 Okubo wrote the following about this image:

Despite reports that the alkaline soil was not good for agricultural purposes, in the spring practically everyone set up a victory garden. Some of the gardens were organized, but most of them were set up anywhere and any way. Makeshift screens were fashioned out of precious cardboard boxes, cartons, and scraps of lumber to protect the plants from the whipping dust storms.

Victory gardens were planted during wartime to help prevent a food shortage by reducing the demands on the country’s food supply. Eating homegrown produce was also important because the trains and trucks were needed to transport soldiers and weapons for the war. To eat food grown in your garden was a display of patriotism and a way for people to contribute to the war effort. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a big supporter of victory gardens and planted one at the White House.

It is interesting to consider that Japanese Americans incarcerated in camps participated in such a patriotic act during a time when they were not being treated fairly as Americans.

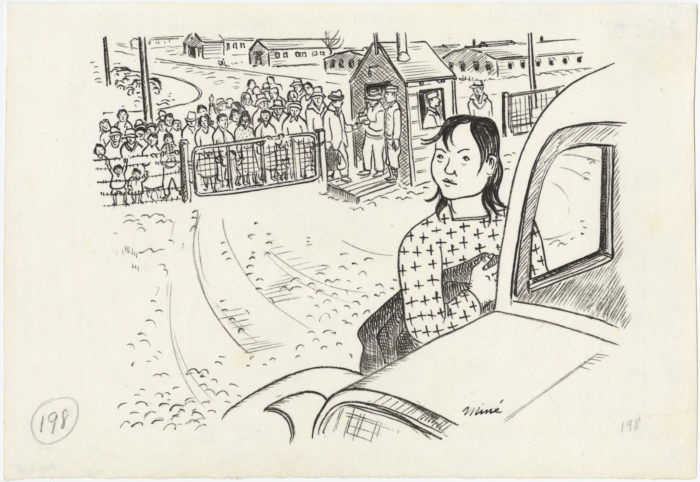

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Boarding the bus to leave camp, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.205)

This object is part of the story Sketches from Within, which is about Justice & Democracy.

The last image in Okubo’s Citizen 13660 book is this one.

- How would you describe what is depicted in this drawing?

- What evidence do you see to support your description?

- The woman in the foreground is the artist, Miné Okubo. How would you describe her facial expression?

- What thoughts might be going through her mind at this moment?

This is what Okubo wrote about this image:

I looked at the crowd at the gate. Only the very old or very young were left. Here I was, alone, with no family responsibilities, and yet fear had chained me to the camp. I thought, “My God! How do they expect those poor people to leave the one place they can call home?” I swallowed a lump in my throat as I waved good-by to them. I entered the bus. As soon as all the passengers had been accounted for, we were on our way. I relived momentarily the sorrows and the joys of my whole evacuation experience, until the barracks faded away into the distance. There was only the desert now. My thoughts shifted from the past to the future.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (2003.294.1)

This object is part of the story Pride and Joy, which is about Dignity.

This object is part of the story Pride and Joy, which is about Dignity.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (96.109.34)

This object is part of the story Pride and Joy, which is about Dignity.

This is a photograph of Mr. Emi with the vanity he described as his “pride and joy.” The back of the photograph indicates the furniture pictured was made at Heart Mountain concentration camp.

- How would you describe his expression?

- What else do you see in this photograph?

- Without the inscription on the back, would you know where this photograph was taken?

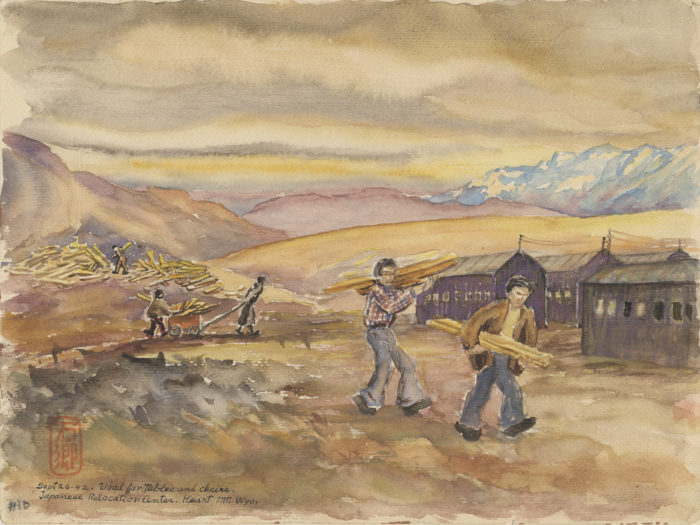

Estelle Ishigo, Untitled (Sept 26-42. Wood for tables and chairs. Japanese Relocation Center. Heart Mt., Wyo.), 1942, watercolor on paper, Japanese American National Museum (94.195.30)

This object is part of the story Pride and Joy, which is about Dignity.

- What do you see in this image?

- Where was this image painted?

- What are the people doing?

- What evidence can you find that tells you what is happening in this painting?

This is a watercolor painting by a Caucasian woman named Estelle Ishigo. Estelle lived at Heart Mountain along with her husband, Arthur. While there, she drew and painted many of her experiences, giving us a view into daily life at the camp.

Japanese American families were removed from their homes and permitted to bring only what they could carry. Despite this, there were some intangible things that could not be taken away from the Japanese Americans.

- Which ones are depicted in this painting?

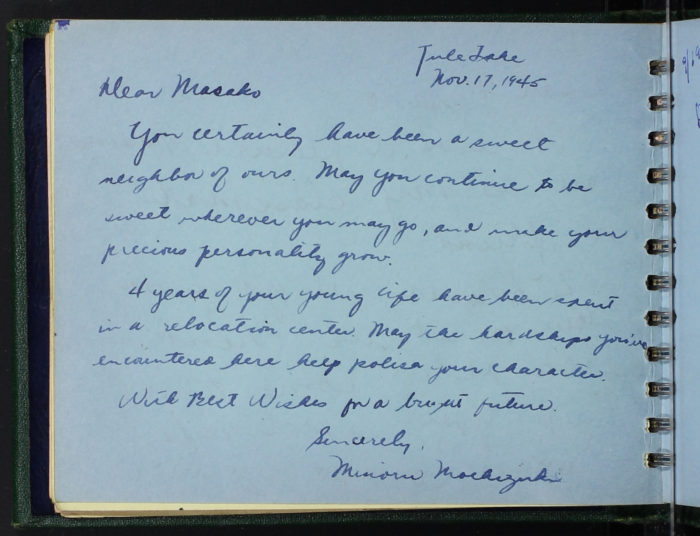

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.9)

This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

Japanese American National Museum, Gifts of Masako Iwawaki Koga (2003.37.2, 2003.37.6, 2003.37.11, 96.14.3)

This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

The wooden pins pictured were made by Masako’s grandmother Tsuya Mukai while incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Tsuya sent them to Tule Lake, California, where her daughter Toshiko and granddaughters Yaeko and Masako were living.

- What do you learn about Tsuya Mukai by looking at these pins?

The tiny decorative geta (Japanese footwear) were made by Masako while incarcerated at Tule Lake. Notice how detailed they are.

- What conclusions can you draw about Masako by looking at these?

- Why do you think Masako made these?

Many crafts emerged from America’s concentration camps as Japanese American inmates found ways to expend their creative energy. The fact of their barbed-wire confinement did little to suppress the Japanese Americans’ desire to bring some normalcy to their mundane camp lives.

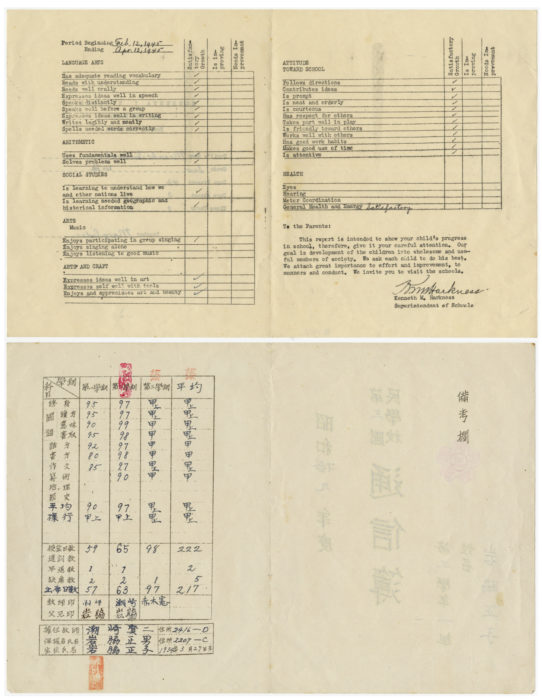

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.6, 96.14.7)

This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

These are two report cards belonging to 11-year-old Masako. They are from her time spent at Tule Lake Segregation Center.

- What do you notice about these cards?

Masako attended school in English, studying subjects such as language arts, arithmetic, social studies, and arts. She also studied Japanese, which is why one of these report cards is in Japanese.

- Based on the evidence in these two documents, what can you learn about Masako?

- Based on the evidence in these two documents, what can you learn about the community at Tule Lake?

- Why would it be important for Masako, a young American of Japanese ancestry, to also study Japanese?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.10)

This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

- Where do you think this photograph was taken?

- Who do you think is depicted in this photograph?

- What visual evidence leads you to these conclusions?

Pictured at the far right is Masako Murakami. She was about 11 years old when this photograph was taken at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California. She is shown here with friends who lived on the same block as she did.

- What expressions do you see on the faces of these individuals?

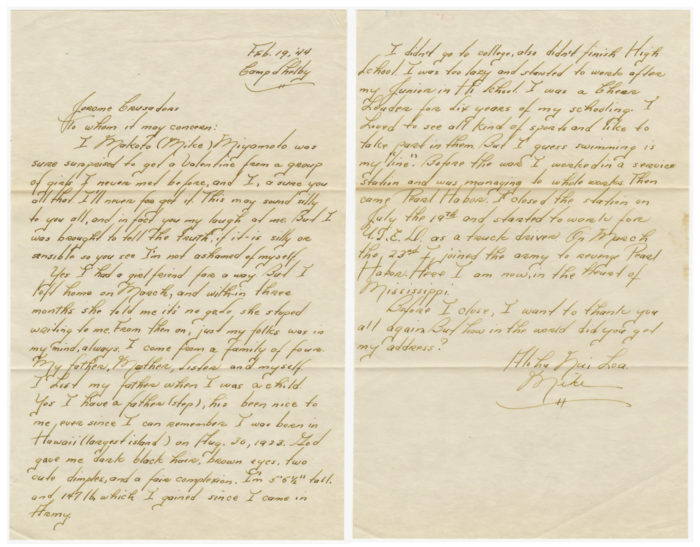

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

Take a look at this letter from 1944.

- To whom is it addressed?

- Who sent it?

- What type of information is being shared?

- Do you think the writer knows the recipients?

While incarcerated in Jerome, Arkansas, a small group of five Sunday school students and their teacher, Mary Nakahara (who later became notable civil-rights activist Yuri Kochiyama), decided to start writing to Japanese Americans serving in the military. This effort grew as other students and parents joined in. They wrote to soldiers whose names they gathered by asking around in their community to find those with family members serving in the military. The letter-writers called themselves the Crusaders.

This page is taken from a scrapbook of letters and cards exchanged between the soldiers and the Crusaders. It was compiled and saved by Rinko Shimasaki, one of the high school students who corresponded with the soldiers.

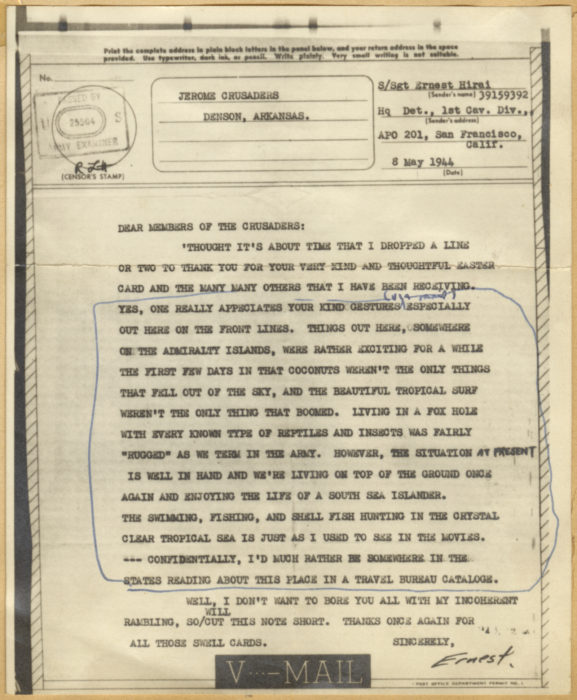

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

This is a letter to the Jerome Crusaders from Sgt. Ernest Hirai.

- What is the tone of this letter?

- By reading this letter, what can you gather about the conditions in which Sgt. Hirai is living?

- Look at the designs on the paper on which the letter is typed. What details do you notice?

- Do you see the censor’s stamp? Why would this letter need to be censored?

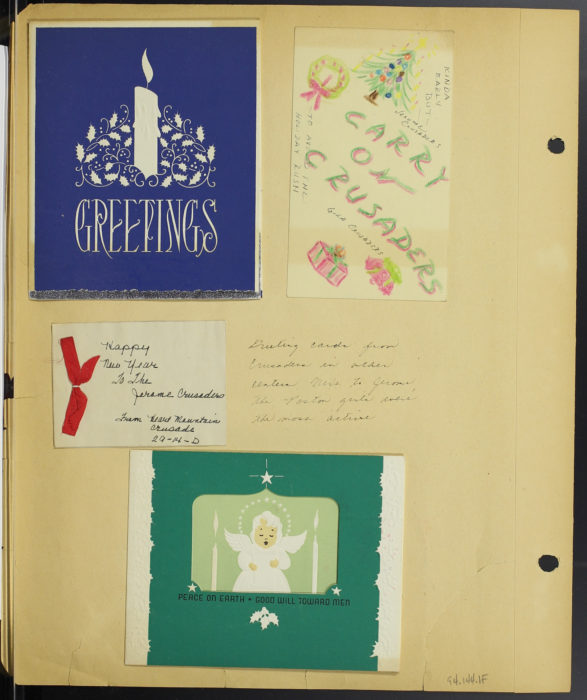

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (96.144.1F)

This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

This is a page from the Crusaders’ scrapbook. Look closely at these greetings.

- To whom are they addressed?

- Who sent them?

The Crusaders expanded beyond Jerome with members in other camps as well.

- What evidence of membership in other camps can you see on this page of greeting cards?

The Crusaders were a strong network of letter writers. Despite the distance between the camps, the Crusaders shared a desire to support the soldiers in their communities and show they cared.

Yuri Kochiyama video interview (June 16, 2003), Japanese American National Museum, DiscoverNikkei.org

This object is part of the story Carry On, Crusaders, which is about Community & Culture.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.8)

This object is part of the story New Year's A-Comin', which is about Community & Culture.

Look closely at this photograph and the handwritten text at the bottom.

- What do you see?

- What evidence in the photograph gives you clues about where this photograph may have been taken?

- Does this photograph convey to you that the New Year holiday is coming?

The individuals in this photograph are making mochi while incarcerated at Gila River, Arizona. Mochi is a Japanese rice cake made by steaming and pounding rice and then forming it into small round shapes, as seen in this photograph. Sticky in texture, it is a very traditional food made and eaten by Japanese families during the New Year holiday. Often families have large gatherings and work together all day making mochi. It is a custom that continues today in many Japanese and Japanese American families.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.8)

This object is part of the story New Year's A-Comin', which is about Community & Culture.

Look closely at this photograph.

- What do you see?

- Do you have any guesses about what is happening in this photograph?

- Is there anything you wonder about what is happening in this photograph?

This photograph was taken at Gila River and shows the part of the mochi-making process in which the rice is steamed in preparation for pounding.

- What do you notice about the people in this photograph?

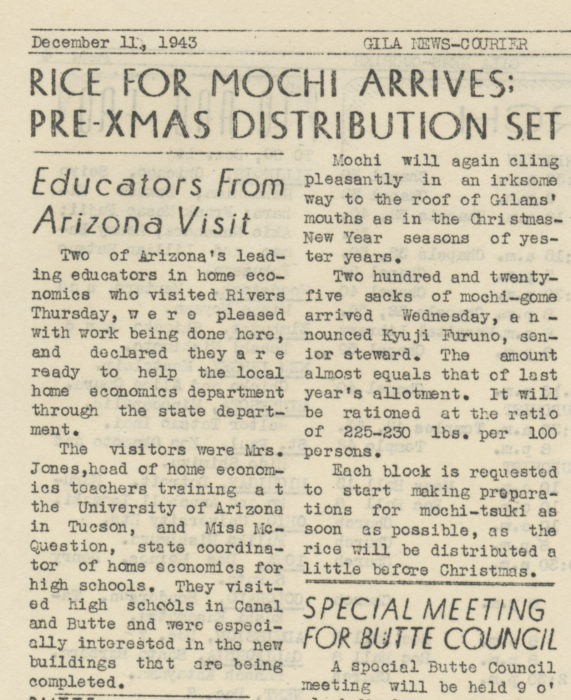

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.2)

This object is part of the story New Year's A-Comin', which is about Community & Culture.

This is a page from the Gila News-Courier, the newspaper printed in the Gila River Concentration Camp in Arizona. Read the article titled “Rice for Mochi Arrives: Pre-Xmas Distribution Set” and consider the importance of this event to the incarcerated community at Gila River.

Here are some definitions that may be helpful as you read the article:

mochi-gome: sweet rice used to make mochi

mochi-tsuki: the making of mochi

Gilans: individuals living at Gila River

Mochi is associated with a happy time of year and mochi-making is an activity that brings Japanese American families and their communities together.

As you read the first sentence, ask yourself what types of feelings you think the Japanese and Japanese Americans associate with mochi.

Hisako Hibi, Untitled (New Year’s Mochi), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Ibuki Hibi Lee (99.63.2)

This object is part of the story New Year's A-Comin', which is about Community & Culture.

- Can you spot the mochi in this painting?

- What else do you see depicted?

- What would you say is the mood of this painting?

This painting was made by an artist named Hisako Hibi. During World War II, she was incarcerated in a concentration camp in Topaz, Utah, and it was there that she painted this image. The formation of two stacked mochi topped with a small citrus is called an okasane. It symbolizes hope for health and prosperity and is often displayed in homes during the New Year season.

- Why might painting a picture of an okasane be important to Hibi while she is in camp?

On the back of this painting is an inscription that reads:

Hisako Hibi. Jan 1943 at Topaz. Japanese without mochi (pounded sweet rice) is no New Year! It was very sad oshogatsu (New Year). So, I painted okazari mochi in the internment camp.

- Now that you know what is written on the back, does it change the mood of this painting for you? If so, how?

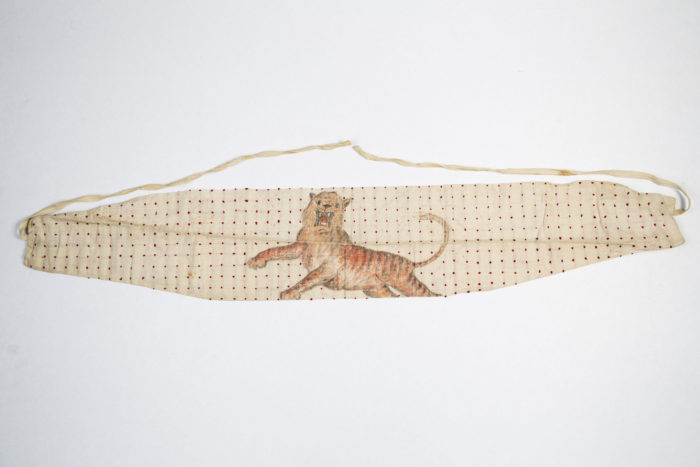

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Susumu Ito (94.306.2)

This object is part of the story A Soldier's Treasure, which is about Identity.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Susumu Ito (94.306)

This object is part of the story A Soldier's Treasure, which is about Identity.

Born in California in 1919 to a family of immigrant tenant farmers, Sus Ito was drafted into the US Army in February 1941. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he was switched to civilian duty while his family was sent to live at Rohwer concentration camp in Arkansas. In the spring of 1943, he was selected to join the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 522nd Field Artillery Battalion. Ito went on to serve in all of the 442nd’s campaigns in Italy, France, and Germany, eventually rising to the rank of lieutenant. His tour of duty included high-profile historical events such as the rescue of the Lost Battalion and the liberation of a subcamp of Dachau.

During his time in Europe, Ito kept three things with him: a small Bible, a senninbari (Japanese 1000-stitch cloth belt traditionally given to soldiers who are going to war) made by his mother at Rohwer, and a 35mm Agfa camera. He took thousands of photographs documenting his life in the military and went to great lengths to preserve the negatives, even having some of them developed at villages he was stationed at along the way. Ito’s vast archive of images taken while on duty during World War II gives a rare and breathtaking look at daily life within the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion of the celebrated all-Japanese American 442nd RCT.

Susumu Ito video interview (July 8, 2015), Japanese American National Museum

This object is part of the story A Soldier's Treasure, which is about Identity.

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (In Camp Jerome), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.9)

This object is part of the story A Soldier's Treasure, which is about Identity.

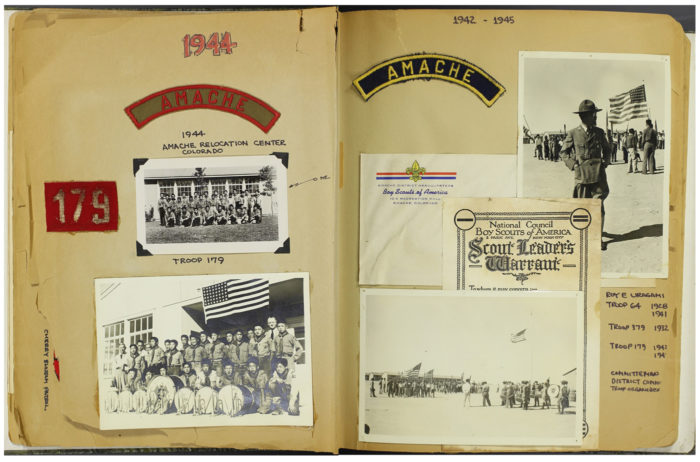

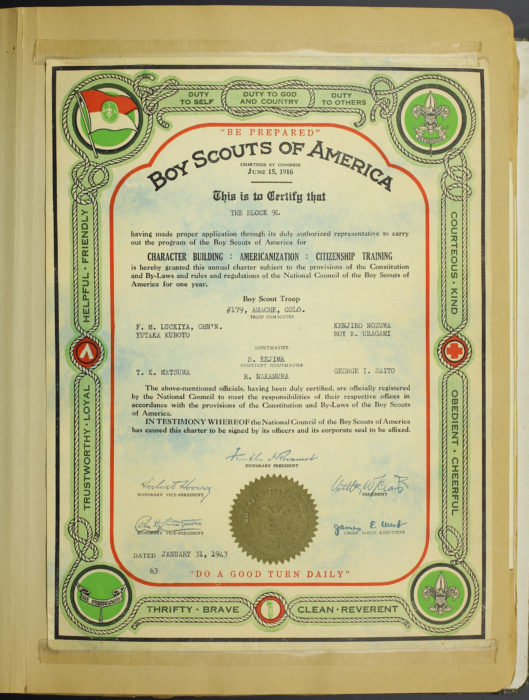

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (2003.86.1)

This object is part of the story Scouts in Camp, which is about Identity.

These are two pages from a 73-page scrapbook documenting three generations of boy scouting in a Japanese American family. The scrapbook was made by Bob Uragami, whose father, Roy, was the first to become involved with scouting; Roy was followed by Bob, and later Bob’s son, Tim.

Look closely at these two pages.

- What do you recognize?

- What things do you wonder about?

- Where were these items used and when were these photographs taken?

- As you look at the photographs, what stands out to you?

- Why do you think Bob decided to include these specific photographs and mementos in his scrapbook?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (2003.86.1)

This object is part of the story Scouts in Camp, which is about Identity.

This Boy Scouts of America certificate was given to the Boy Scout troop of Japanese Americans incarcerated at Amache, Colorado. Look closely at the text and designs on this certificate.

- How would you describe the overall tone of this certificate?

- Which words stand out to you?

- How would you have felt if you received this certificate from the Boy Scouts of America while you were imprisoned by the US government?

- How might words such as “duty to country” and “Americanization” feel different to the members of this troop under the conditions in which they lived?

Bob Uragami video interview, Japanese American National Museum

This object is part of the story Scouts in Camp, which is about Identity.

In this video, Bob Uragami speaks about the drum that was used by his Boy Scout troop while incarcerated at Amache. The drum can also be seen in one of the images in the scrapbook. As you watch this video, consider what Mr. Uragami says about the flags depicted on the drum.

When he refers to the “meatball,” he is using a nickname for the Japanese flag, which has one large circle on it.

- How does the story about the flags reflect the identity of this group of Boy Scouts?

- How does the story about the burial suit reflect the identity of Mr. Uragami’s father?

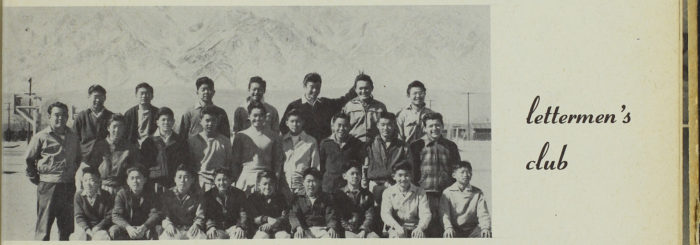

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (99.2.8B)

This object is part of the story Scouts in Camp, which is about Identity.

- What do you see depicted in this image?

- Who do you think the man in the foreground is?

- Where do you think this photograph was taken?

- What evidence in the photograph helps you draw these conclusions?

This photograph was taken at Amache Concentration Camp. Roy Uragami, the father of Bob Uragami, is pictured in his uniform in the foreground.

- How would you describe Roy Uragami’s expression?

- What thoughts might be going through his head at this moment?

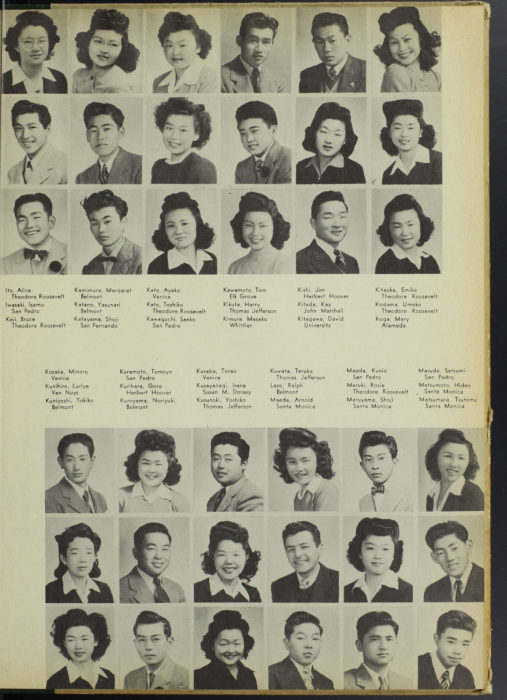

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

This is a page from the 1944 Manzanar High School yearbook. Look carefully at these faces and names.

- What do you notice?

As one might expect, almost all of the students pictured in the yearbook are Japanese American. There is one student, however, who is not. Find the photograph of Ralph Lazo. Lazo is of Mexican and Irish descent.

- Why do you think he is pictured in this yearbook from Manzanar Concentration Camp?

- What events might have led to him living in Manzanar?

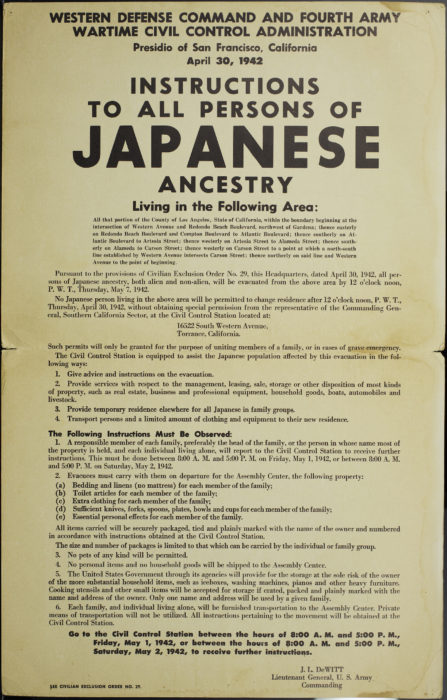

“Public Proclamation No. 29” (April 30, 1942), Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.13)

This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

Read the text of this document carefully. This is a Civilian Exclusion Order. In 1942, these posters were placed in public areas all along the West Coast of the United States.

- To whom are these instructions directed?

- If you were a person of Japanese ancestry, how would you feel as you read these posters?

- If your best friend was a person of Japanese ancestry, how would you feel as you read these posters?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

Although Ralph Lazo was not Japanese American, many of his friends at Belmont High School in Los Angeles were. When the Civilian Exclusion Order called for all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast to be incarcerated in concentration camps, Ralph witnessed many of his good friends forcibly removed from their homes and sent to camp. He considered his Japanese American friends to be his equals. Realizing the incarceration was unjust and wishing to support his friends, Ralph decided he would go to camp as well. He ended up living at Manzanar and going to high school there.

Take a look at this photograph from the Manzanar High School yearbook.

- Can you find Ralph Lazo?

- Does he stand out from the others in a drastic way?

- How would you describe his mood?

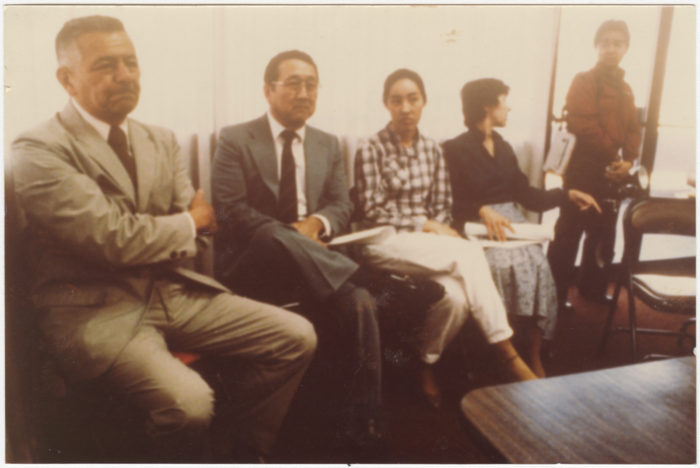

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Hannah Tomiko Holmes (94.181.134)

This object is part of the story Friends for Life, which is about Dissent.

This snapshot was taken during a press conference for the National Council for Japanese American Redress, many years after the teenaged Ralph Lazo joined his friends at Manzanar. The council was formed in 1979 to obtain restitution for Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II. In this photograph, Lazo is shown on the left.

- By looking at this photograph taken decades after World War II, what do you learn about Ralph Lazo as an adult?

Lazo’s presence in this photograph shows how even decades after World War II he continued to support his Japanese American friends and the Japanese American community.

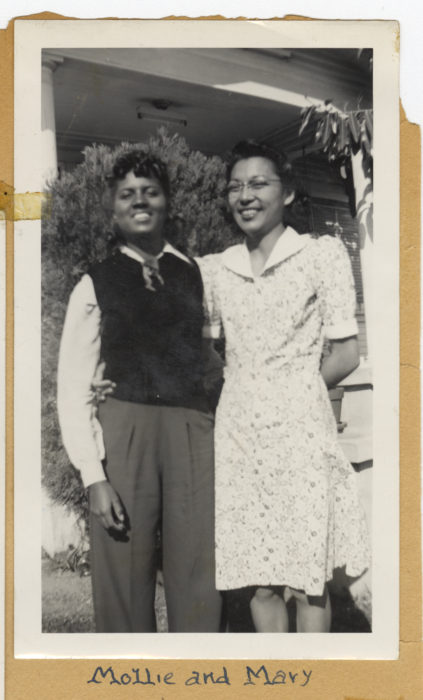

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.2A)

This object is part of the story A Friend Back Home, which is about Loyalty.

- As you look at this photograph, what do you notice?

- What are some things that give you a sense of the time period?

- What are the names of these two individuals?

- Do you have any guesses about who they are and what their relationship is to one another?

- How would you describe the mood of this photograph?

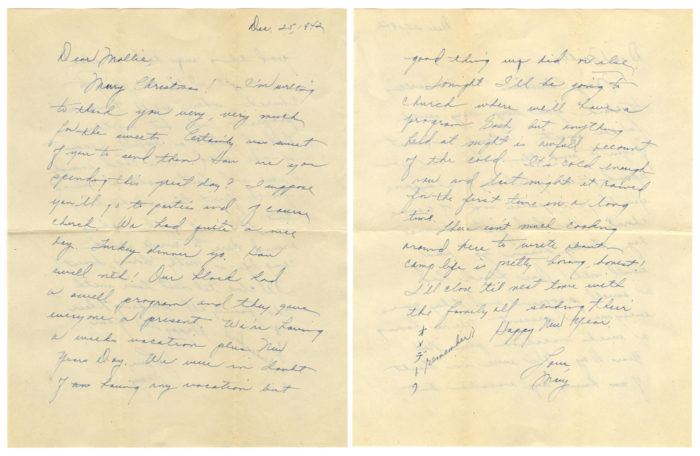

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.5F)

This object is part of the story A Friend Back Home, which is about Loyalty.

Carefully read this letter and consider the following questions:

- Who wrote this letter?

- To whom was the letter written?

- What information can you gather about who Mollie is? Where is she?

- What information can you gather about who Mary is? Where is she?

- What are some of the topics written about in this letter?

- Based on the content of this letter, what kind of camp is Mary referring to?

Mollie Wilson lived in Los Angeles and attended Roosevelt High School. Many of her Japanese American friends were forced to move during World War II. She would often write to her incarcerated friends, such as Mary Murakami.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.5B)

This object is part of the story A Friend Back Home, which is about Loyalty.

Letters provide a great window into history. Even from an envelope alone, there is much information to be gathered. This is the envelope for a letter from Mary to Mollie.

Look closely at the envelope.

- What do you notice?

- Based on the return address and cancellation stamp, can you tell where Mary was living when she sent this letter?

- Why do you think one address is crossed out and replaced by another?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.24)

This object is part of the story A Friend Back Home, which is about Loyalty.

This is a photograph of Sandie Saito. Like Mary, she was a friend of Mollie’s from Roosevelt High School. Sandie is pictured here in a Roosevelt letterman sweater while incarcerated at Amache, Colorado. Sandie sent this photo to Mollie from Amache. In the corner she wrote, “To Molly, Just, Sandie,” and on the back of the photograph it says, “This picture was taken way at the west end of the football field.”

Imagine being a young person who is forced to abruptly migrate to an unknown place, far from everything familiar.

- What people, places, activities, or things would you miss about your daily life?

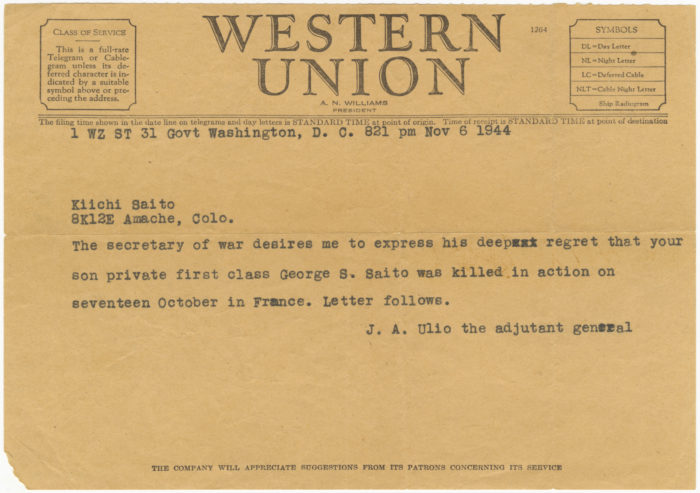

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.49.33)

This object is part of the story Telegram to a Father, which is about Loyalty.

Read this document closely.

This is a telegram to Kiichi Saito. Three of Mr. Saito’s sons served in the United States Army during World War II including his son George, who is referenced in this telegram.

- Where was Mr. Saito living at the time he received this telegram?

- How would you describe the tone of this message?

- What questions do you have after reading this document?

Mary Saito Tominaga and Kazuo Saito video interview (November 2, 2010), Japanese American National Museum

This object is part of the story Telegram to a Father, which is about Loyalty.

Watch this video of George Saito’s brother Kazuo and sister, Mary.

- Based on what they say about him in this clip, why do you think George decided to join the army?

- What can you gather about George from this clip? What type of person was he?

- Where was the Saito family living when George left to join the army?

- Did you notice the photograph of George and his brothers Calvin and Shozo? How are they all dressed in the photograph?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.49.41)

This object is part of the story Telegram to a Father, which is about Loyalty.

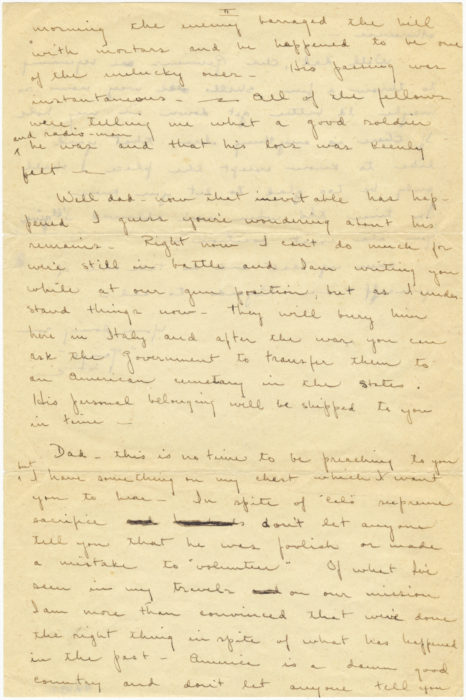

In 1944, while attacking a hill in Italy, George’s younger brother Calvin, who was also serving in the army, was struck and killed. This is from a letter George sent home to console his grief-stricken father.

Dad—this is no time to be preaching to you but I have something on my chest which I want you to hear In spite of Cal’s supreme sacrifice, don’t let anyone tell you that he was foolish or made a mistake to “volunteer.” Of what I’ve seen in my travels, on our mission, I am more than convinced that we’ve done the right thing in spite of what has happened in the past. America is a damn good country and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

– George Saito, letter to his father, July 11, 1944

- What do you think is the main message George has for his father?

- If you were in George’s position, do you think you would share his sentiments? Why or why not?

- Why do you think George felt it necessary to write these words?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.6.77)

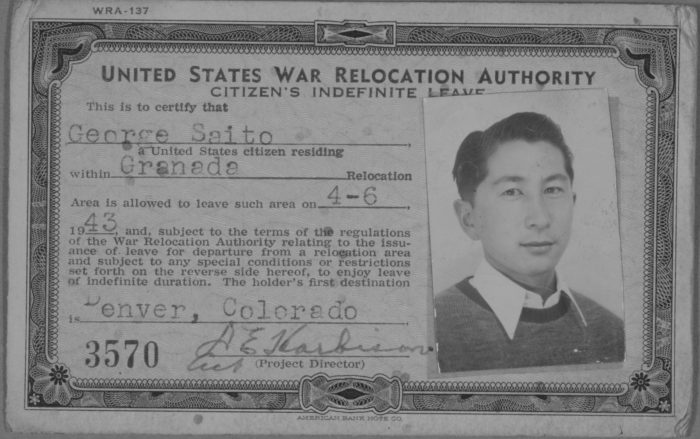

This object is part of the story Telegram to a Father, which is about Loyalty.

- Does this document give any clue as to who George Saito is?

- Does he look like a young man or an older man?

- What country is he a citizen of?

- What might prompt a government to monitor its citizens in this way?

- At the time this document was issued, where was George residing?

- Does such a document make you question the rights and limitations of an American citizen?

This document is George’s indefinite leave card, issued by the government as a way to monitor any subversive behavior in its American-born citizens of Japanese ancestry. This card gave George permission to leave Amache concentration camp. Soon after its issuance, George enlisted in the United States Army and served in the segregated 442nd RCT in Europe.

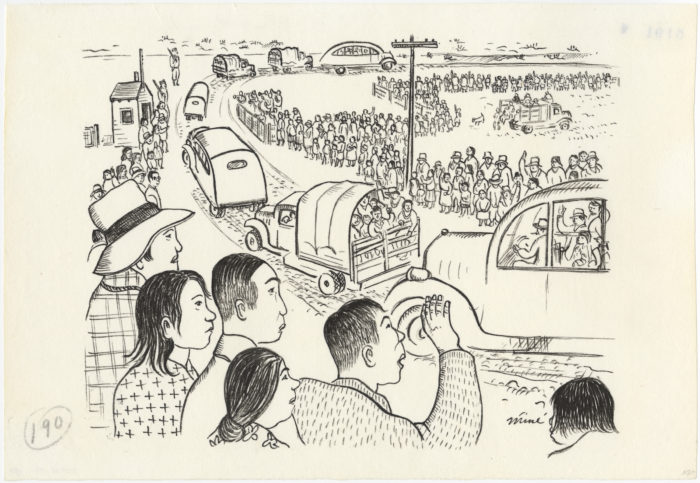

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Departure and segregation of pro-Japanese to Tule Lake, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–44), c. 1942–44, ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.197)

This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

Look carefully at this drawing by Miné Okubo. Examine all the details in the foreground, middleground, and background.

- What is depicted in this drawing?

- Where might all the people in the vehicles be leaving from?

- Where might they be going?

- How would you describe the expressions on the faces you see?

- What questions do you have about this image?

In her book Citizen 13660, originally published in 1946, Ms. Okubo wrote the following about her image:

The program of segregation was now instituted. One of its purposes was to protect loyal Japanese Americans from the continuing threats of pro-Japanese agitators. Tule Lake, one of the ten original centers, was chosen as a segregation center for the disloyal. In the fall of 1943 thirteen hundred Topazians (about one tenth of the total) were sent there. The group included all who had said they wished to return to Japan; the “no, nos,” that is, those who would not change their unsatisfactory answers to the questionnaire when they were given a chance to do so; all who remained under suspicion of disloyalty after investigation by the War Relocation Authority and the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and close relatives who would rather be segregated with their families than separated from them.

Whatever decision was made, families suffered deeply.

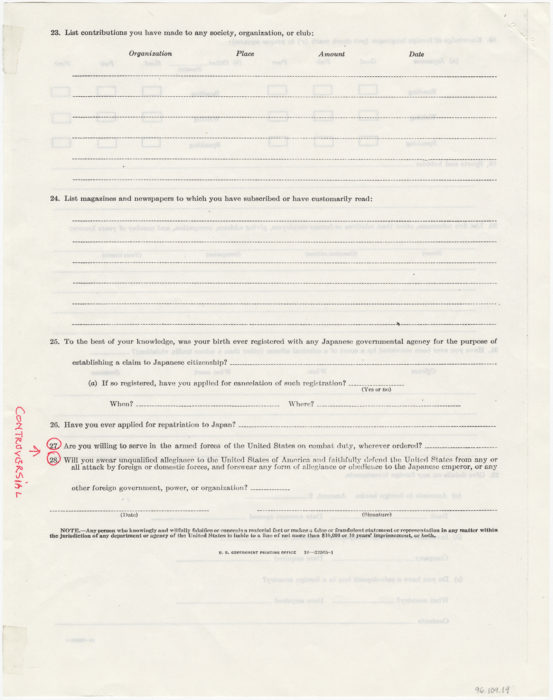

Loyalty questionnaire, 1943, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (96.109.19)

This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

This is a page of the loyalty questionnaire administered to Japanese Americans while they were imprisoned in concentration camps. Take a look at questions 27 and 28.

Imagine if you were a young American citizen of Japanese descent incarcerated in a concentration camp and presented with these questions.

- How would you respond?

- Why would you respond in this way?

- What questions or concerns would you have?

The War Department and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) scored the answers to the loyalty questionnaire by ranking them according to Americanness and Japaneseness. Especially problematic were questions 27 and 28. Question 27 asked if Nisei men were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered and asked everyone else if they would be willing to serve in other ways, such as joining the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Question 27 was an insulting question to some who were angry about being incarcerated. Question 28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. The problem this question posed was that Issei were not allowed to become American citizens—if they forswore allegiance to the Japanese emperor, they would become stateless, without any connection to a government; and the Nisei, who were American citizens, never had any allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

At most of the incarceration camps, Japanese Americans answered “yes” to both questions 27 and 28. However, many were uncomfortable making this agreement to serve in the military at the same time that the US government was suspending their constitutional rights. For this reason, there were some who answered “no” to both questions. Labeled as disloyal, they were sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center.

LIFE Magazine Vol. 16, No. 12 (March 20, 1944), Japanese American National Museum, Gift in Memory of Hugo W. Wolter (97.329.96)

This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

Without reading the caption, look closely and answer the following questions:

- How would you describe the individuals in this photograph?

- What things do you see in the space they are in?

- Can you guess where this photograph was taken?

Now read the caption of the photograph.

- Does any of the information surprise you? If so, which information and why?

- How does the caption contrast with the image?

- What message do you think the photographer is trying to convey with this image?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Charles and Lois Ferguson (93.3.1)

This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

- What would you say is the tone of this speech?

- What are the main messages conveyed?

- What can you conclude about Mr. Kurihara based on his words?

- To whom do you think this speech is being directed?

This is an excerpt from a speech written by Joe Kurihara while he was an inmate at Manzanar concentration camp. Mr. Kurihara was born in Hawai‘i and served in the United States Army during World War I. During his incarceration, Mr. Kurihara was an outspoken dissident leader against the US government’s unjust imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

Due to his actions as an agitator, Mr. Kurihara was transferred from Manzanar to Tule Lake, the segregated center for Japanese Americans who were alleged to be disloyal.

Mr. Kurihara’s anger eventually led him to renounce his US citizenship and go to Japan, where he lived out the remainder of his life.