Silent Skater

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Dave Tatsuno in memory of Walter Honderick (91.74.1–8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Watch this short video clip.

- What is she doing?

- Where do you think she might be? Why do you think that?

- How might you describe her mood?

- Who do you think recorded this video?

- What else do you observe?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Dave Tatsuno in memory of Walter Honderick (91.74.1–8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Watch this short video clip from the Topaz War Relocation Center.

- How is the environment similar to or different from where you live?

The Topaz War Relocation Center was located in Millard County in West Central Utah, 16 miles northwest of the town of Delta and 125 miles southwest of Salt Lake City. Situated at 4,600 feet of elevation, the camp occupied 19,800 acres of extremely flat terrain in the Sevier Desert. Dust was a major problem, as were extreme temperatures that ranged from 106 degrees in summer to below zero in winter.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Dave Tatsuno in memory of Walter Honderick (91.74.1–8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Watch this video and think about what it might have been like to live in this community.

At its peak, Topaz housed 8,130 Japanese Americans. Most of those held in Topaz were from the San Francisco Bay area in California: Alameda, San Francisco, and San Mateo Counties.

Each residential block had twelve housing barracks, a dining hall, a bathroom, a laundry facility, a recreation hall, and a block manager’s office. Each block also had a community mess hall, where almost everyone ate their meals. Some inmates were able to get jobs as cooks, dishwashers, or other staff positions within the camps, but many did not work. For the Issei, who often worked six or seven days a week, this was the most free time they ever had since immigrating to the United States. The inmates kept themselves busy taking classes like English and citizenship, or working on gardens; many did arts and crafts to pass the time. If they wanted to buy things they couldn’t get at the camps, they ordered them from catalogs for Sears or Montgomery Ward. At Topaz, some ordered ice skates by mail to use at the camp rink.

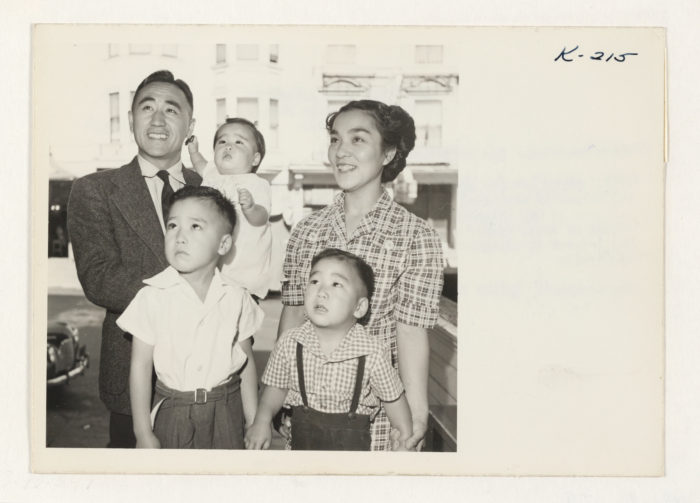

“War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Series 16: Resettlement” (Volume 81, Section K, WRA no. 215), courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Click to open full-size image in new tab.The person who took these home movies was Dave Tatsuno (1913–2006). Mr. Tatsuno was well known within the Bay Area’s Japanese American community for operating the Nichi Bei Bussan stores in San Jose and San Francisco, California. The Tatsuno home movie collection documents activities in Topaz concentration camp as well as pre-WWII festivals, sporting events, family outings, holidays, celebrations, and the Tatsuno family business, the Nichi Bei Bussan.

In 1942, Mr. Tatsuno and his family were incarcerated at the Topaz War Relocation Center in the Utah desert. Over the next three years, shooting covertly with a contraband camera, he recorded everyday life in the dust-blown barracks community that at its height was home to more than 8,000 Americans of Japanese descent. Mr. Tatsuno’s haunting footage was later compiled into a 48-minute silent film, Topaz. In 1996, Topaz was placed on the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. Mr. Tatsuno’s film was only the second home movie to be included in the registry, which is primarily dedicated to Hollywood classics like Citizen Kane and Casablanca. The first home movie to be included in the registry was Abraham Zapruder’s film of President John F. Kennedy’s 1963 assassination.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Dave Tatsuno in memory of Walter Honderick (91.74.1–8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.One can infer that the young woman in the video clip enjoyed the solitude of ice skating alone. Amidst the chaos of camp—the people, the lines, and the dust storms—she seems to have found a peaceful moment to herself, perhaps to reclaim nicer memories. There is dignity in both her demeanor and the elegant way she is dressed; a stark contrast to the camp and its rows and rows of barracks.

Return to Dignity