Justice Democracy2

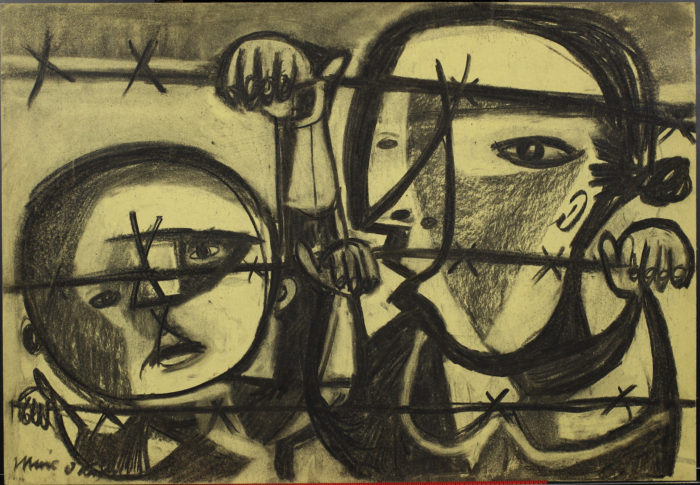

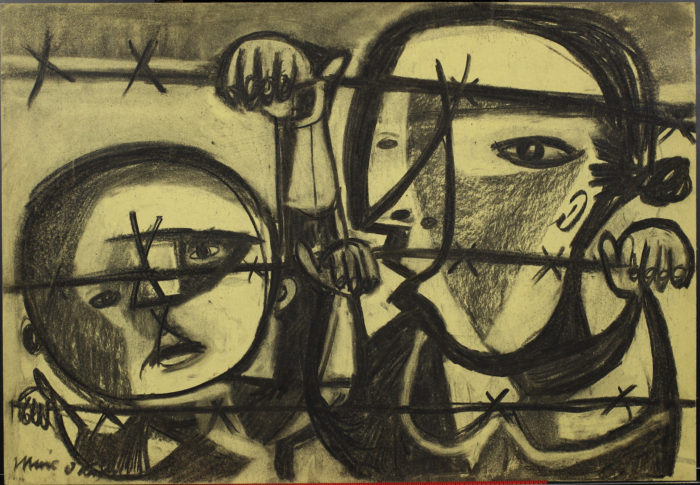

Miné Okubo, Untitled, n.d., charcoal on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What do you see depicted in this charcoal drawing by Miné Okubo?

- Based on body language and facial expressions, what can you infer about these figures?

- What emotions are evoked by this drawing?

Miné Okubo is a Japanese American artist best known for her black and white ink drawings, though this sketch is done in charcoal. As you view more of her works on this website, consider how her artistic tools change the mood of her drawings and why she may have chosen to do this particular scene in charcoal rather than ink.

- How is this sketch different from or similar to the rest of her work?

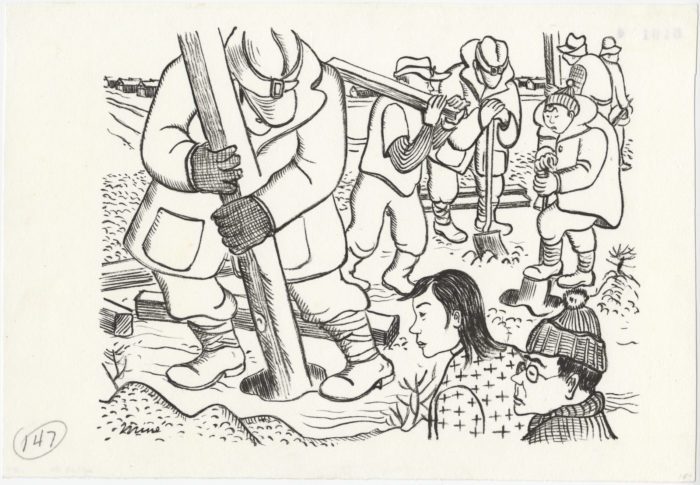

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Fence and watchtower construction, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.154)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a drawing of the Topaz concentration camp by Miné Okubo. She documented her personal story as a Topaz inmate in great detail through her drawings and paintings. Many of her drawings were published in an autobiographical book titled Citizen 13660. In this book, Okubo provided descriptions to accompany each image. Here’s what she wrote about this image:

Fence posts and watch towers were now constructed around the camp by the evacuees to fence themselves in.

- What thoughts do you have as you read this description?

- What questions do you have?

- How does this image heighten the sense of injustice in incarcerating people without cause?

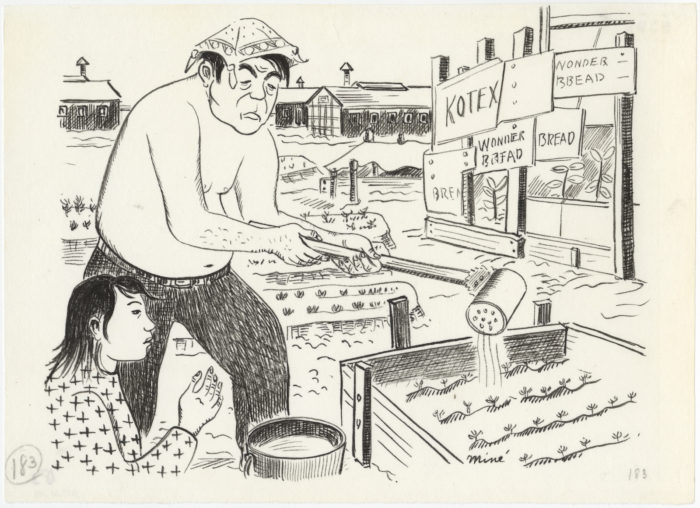

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Victory gardens, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2000.62.190)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is another drawing by Miné Okubo that depicts life at Topaz.

- What do you think the individuals in this drawing are doing?

- Where are they?

- Can you tell what the climate there is like by looking at this drawing?

In Citizen 13660 Okubo wrote the following about this image:

Despite reports that the alkaline soil was not good for agricultural purposes, in the spring practically everyone set up a victory garden. Some of the gardens were organized, but most of them were set up anywhere and any way. Makeshift screens were fashioned out of precious cardboard boxes, cartons, and scraps of lumber to protect the plants from the whipping dust storms.

Victory gardens were planted during wartime to help prevent a food shortage by reducing the demands on the country’s food supply. Eating homegrown produce was also important because the trains and trucks were needed to transport soldiers and weapons for the war. To eat food grown in your garden was a display of patriotism and a way for people to contribute to the war effort. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a big supporter of victory gardens and planted one at the White House.

It is interesting to consider that Japanese Americans incarcerated in camps participated in such a patriotic act during a time when they were not being treated fairly as Americans.

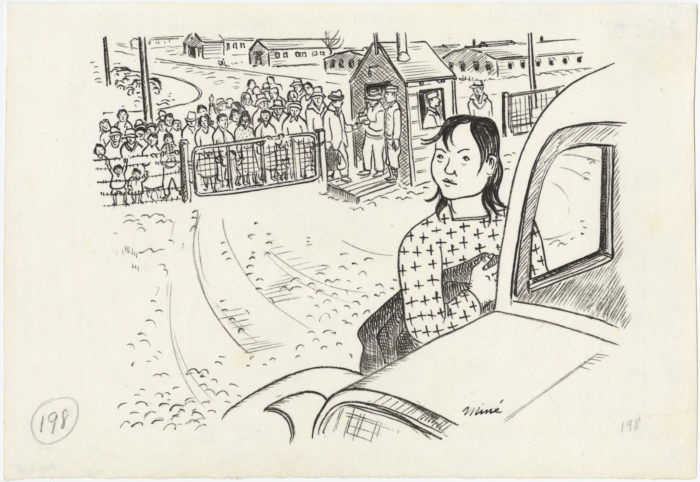

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Boarding the bus to leave camp, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.205)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.The last image in Okubo’s Citizen 13660 book is this one.

- How would you describe what is depicted in this drawing?

- What evidence do you see to support your description?

- The woman in the foreground is the artist, Miné Okubo. How would you describe her facial expression?

- What thoughts might be going through her mind at this moment?

This is what Okubo wrote about this image:

I looked at the crowd at the gate. Only the very old or very young were left. Here I was, alone, with no family responsibilities, and yet fear had chained me to the camp. I thought, “My God! How do they expect those poor people to leave the one place they can call home?” I swallowed a lump in my throat as I waved good-by to them. I entered the bus. As soon as all the passengers had been accounted for, we were on our way. I relived momentarily the sorrows and the joys of my whole evacuation experience, until the barracks faded away into the distance. There was only the desert now. My thoughts shifted from the past to the future.

Miné Okubo, Untitled, n.d., charcoal on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In the preface to the 1983 edition of her book Citizen 13660, Okubo wrote:

I was an American citizen, and because of the injustices and contradictions nothing made much sense, making things comical in spite of the misery.

- In what ways do you see this sentiment reflected in her drawings?

Okubo also wrote:

I am often asked, why am I not bitter and could this happen again? I am a realist with a creative mind, interested in people, so my thoughts are constructive. I am not bitter. I hope that things can be learned from this tragic episode, for I believe it could happen again.

—Miné Okubo, preface to the 1983 edition of Citizen 13660

- If you experienced what Okubo experienced by being incarcerated, and witnessed all that she did, do you think you would have feelings of bitterness? Why or why not?

- Do you believe that the incarceration of a group of people could happen again in the United States?

- Why do you think this could or could not happen?

- Does Okubo’s attitude provide any reassurance that injustices can be remedied even if not eliminated?