Tule Lake

Location: Newell, Calif.

Peak population: 18,789

Date opened: May 27, 1942

Date closed: March 20, 1946

The Tule Lake War Relocation Center was initially setup as a camp but later became a segregation center for the special imprisonment of Japanese Americans who were thought to be “disloyal” to the US. The first 500 people to be sent to Tule Lake were from the Portland and Puyallup Assembly Centers. Others then arrived from the Marysville, Pinedale, Pomona, Sacramento, and Salinas Assembly Centers in California, while some were sent directly from the southern San Joaquin Valley. After it became a segregation center, the camp held people from California, Hawaiʻi, Washington, and Oregon. This was the only camp to have a stockade, or military-style prison.

The camp is located at an elevation of 4,000 feet on a flat, treeless area in Modoc County, 35 miles southeast of Klamath Falls, Oregon, and 10 miles from the town of Tulelake—the town is spelled as one word and the concentration camp as two. Mt. Shasta is 50 miles away and visible on a clear day. The soil is sandy loam; vegetation is sparse grass and sagebrush. Winters are long and cold, while summers are hot and dry.

Tule Lake was the last camp to close.

For more info about Tule Lake, click here.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.9)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

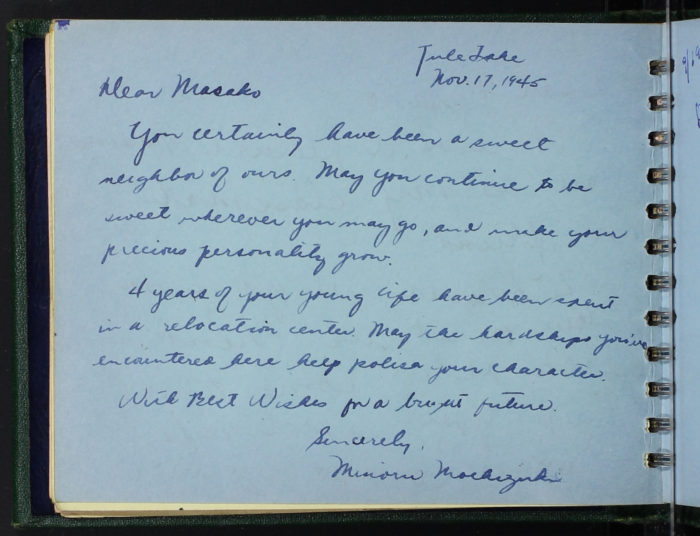

This is a page from an autograph book belonging to Masako Murakami (née Iwawaki). As you read this entry, ask yourself:

- Where was this written?

- When was it written?

- To whom was it written?

- By whom was it written?

- What do you know about Masako and Minoru by reading this text?

Japanese American National Museum, Gifts of Masako Iwawaki Koga (2003.37.2, 2003.37.6, 2003.37.11, 96.14.3)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.

This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

The wooden pins pictured were made by Masako’s grandmother Tsuya Mukai while incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Tsuya sent them to Tule Lake, California, where her daughter Toshiko and granddaughters Yaeko and Masako were living.

- What do you learn about Tsuya Mukai by looking at these pins?

The tiny decorative geta (Japanese footwear) were made by Masako while incarcerated at Tule Lake. Notice how detailed they are.

- What conclusions can you draw about Masako by looking at these?

- Why do you think Masako made these?

Many crafts emerged from America’s concentration camps as Japanese American inmates found ways to expend their creative energy. The fact of their barbed-wire confinement did little to suppress the Japanese Americans’ desire to bring some normalcy to their mundane camp lives.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.6, 96.14.7)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

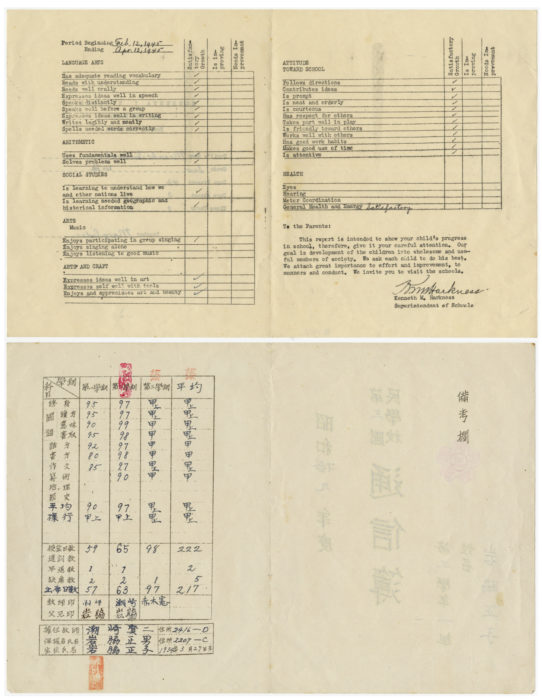

These are two report cards belonging to 11-year-old Masako. They are from her time spent at Tule Lake Segregation Center.

- What do you notice about these cards?

Masako attended school in English, studying subjects such as language arts, arithmetic, social studies, and arts. She also studied Japanese, which is why one of these report cards is in Japanese.

- Based on the evidence in these two documents, what can you learn about Masako?

- Based on the evidence in these two documents, what can you learn about the community at Tule Lake?

- Why would it be important for Masako, a young American of Japanese ancestry, to also study Japanese?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.10)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story Childhood Incarcerated, which is about Community & Culture.

- Where do you think this photograph was taken?

- Who do you think is depicted in this photograph?

- What visual evidence leads you to these conclusions?

Pictured at the far right is Masako Murakami. She was about 11 years old when this photograph was taken at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California. She is shown here with friends who lived on the same block as she did.

- What expressions do you see on the faces of these individuals?

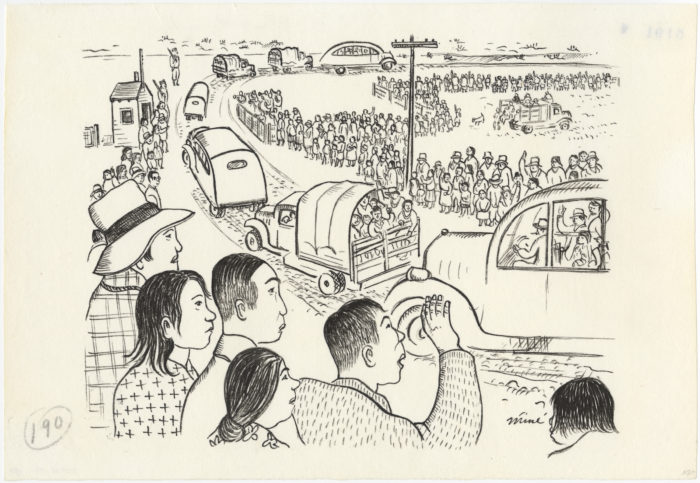

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Departure and segregation of pro-Japanese to Tule Lake, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–44), c. 1942–44, ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.197)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

Look carefully at this drawing by Miné Okubo. Examine all the details in the foreground, middleground, and background.

- What is depicted in this drawing?

- Where might all the people in the vehicles be leaving from?

- Where might they be going?

- How would you describe the expressions on the faces you see?

- What questions do you have about this image?

In her book Citizen 13660, originally published in 1946, Ms. Okubo wrote the following about her image:

The program of segregation was now instituted. One of its purposes was to protect loyal Japanese Americans from the continuing threats of pro-Japanese agitators. Tule Lake, one of the ten original centers, was chosen as a segregation center for the disloyal. In the fall of 1943 thirteen hundred Topazians (about one tenth of the total) were sent there. The group included all who had said they wished to return to Japan; the “no, nos,” that is, those who would not change their unsatisfactory answers to the questionnaire when they were given a chance to do so; all who remained under suspicion of disloyalty after investigation by the War Relocation Authority and the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and close relatives who would rather be segregated with their families than separated from them.

Whatever decision was made, families suffered deeply.

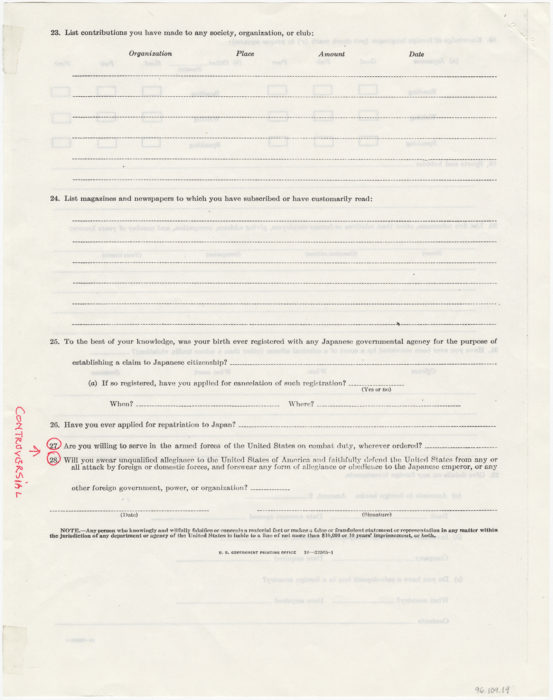

Loyalty questionnaire, 1943, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (96.109.19)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

This is a page of the loyalty questionnaire administered to Japanese Americans while they were imprisoned in concentration camps. Take a look at questions 27 and 28.

Imagine if you were a young American citizen of Japanese descent incarcerated in a concentration camp and presented with these questions.

- How would you respond?

- Why would you respond in this way?

- What questions or concerns would you have?

The War Department and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) scored the answers to the loyalty questionnaire by ranking them according to Americanness and Japaneseness. Especially problematic were questions 27 and 28. Question 27 asked if Nisei men were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered and asked everyone else if they would be willing to serve in other ways, such as joining the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Question 27 was an insulting question to some who were angry about being incarcerated. Question 28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. The problem this question posed was that Issei were not allowed to become American citizens—if they forswore allegiance to the Japanese emperor, they would become stateless, without any connection to a government; and the Nisei, who were American citizens, never had any allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

At most of the incarceration camps, Japanese Americans answered “yes” to both questions 27 and 28. However, many were uncomfortable making this agreement to serve in the military at the same time that the US government was suspending their constitutional rights. For this reason, there were some who answered “no” to both questions. Labeled as disloyal, they were sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center.

LIFE Magazine Vol. 16, No. 12 (March 20, 1944), Japanese American National Museum, Gift in Memory of Hugo W. Wolter (97.329.96)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

Without reading the caption, look closely and answer the following questions:

- How would you describe the individuals in this photograph?

- What things do you see in the space they are in?

- Can you guess where this photograph was taken?

Now read the caption of the photograph.

- Does any of the information surprise you? If so, which information and why?

- How does the caption contrast with the image?

- What message do you think the photographer is trying to convey with this image?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Charles and Lois Ferguson (93.3.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is part of the story A Community Divided, which is about Citizenship.

- What would you say is the tone of this speech?

- What are the main messages conveyed?

- What can you conclude about Mr. Kurihara based on his words?

- To whom do you think this speech is being directed?

This is an excerpt from a speech written by Joe Kurihara while he was an inmate at Manzanar concentration camp. Mr. Kurihara was born in Hawai‘i and served in the United States Army during World War I. During his incarceration, Mr. Kurihara was an outspoken dissident leader against the US government’s unjust imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

Due to his actions as an agitator, Mr. Kurihara was transferred from Manzanar to Tule Lake, the segregated center for Japanese Americans who were alleged to be disloyal.

Mr. Kurihara’s anger eventually led him to renounce his US citizenship and go to Japan, where he lived out the remainder of his life.