Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look closely at this image.

- What do you observe?

- What is depicted?

Consider clothing, background, mood, composition, and color.

- Who might this person be?

- What makes you say that?

- What is the setting for this image?

- What makes you say that?

- What does the writing in the lower left corner say?

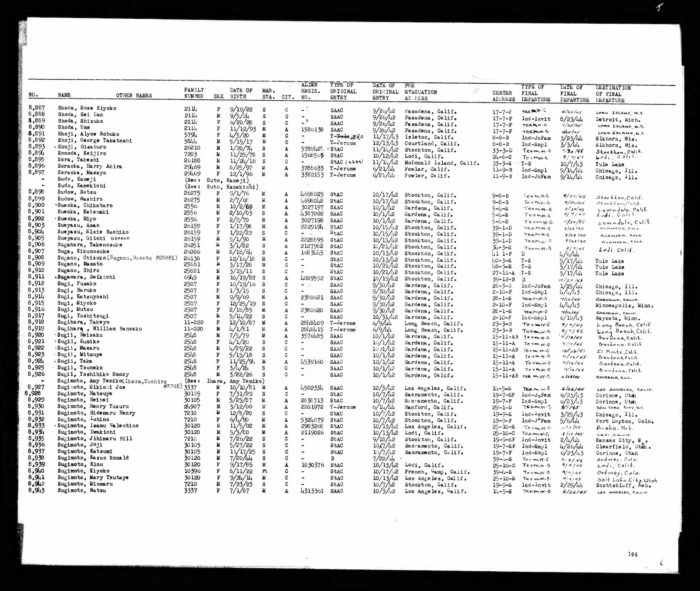

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- Does this historical document give you a better sense of who H. Sugimoto is?

- What new evidence do you have about him?

- Where did he live before World War II?

- Where did he go after World War II?

Henry Sugimoto, quoted in Kristine Kim, Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 55.

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What does this quotation by Sugimoto say about him?

Japanese Americans could not bring cameras of any kind into the camps, preventing the documentation of their treatment and living conditions; even artistic representation of life in the camps was considered suspect. Still, the moment of his arrival at Fresno, Henry Sugimoto resumed sketching and painting despite his worries about surveillance and arrest. Mr. Sugimoto’s anxiety was outweighed by the sense of purpose he found: his skill as an artist made it possible for him to record, for history, the experiences of Japanese Americans in the camps. As he remarked later in life:

“I depicted camp life . . . with an artist’s sense of mission.”

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1982, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.99)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look closely at this image, also a self-portrait by Henry Sugimoto. This was painted in 1982, almost forty years after the other self-portrait.

- What do you observe?

- Do you see the medals in this portrait?

Mr. Sugimoto was awarded many honors during his life, including the medals shown here.

- Why do you think he included the medals in this portrait?

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.5); Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1982, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.99)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- In what ways are these two images similar?

- In what ways are they different?

- Would you say that a sense of dignity is conveyed in these self-portraits? If so, how?

The portrait of the artist in the beret is Untitled (Self Portrait in Camp). It was painted by Mr. Sugimoto in 1943 while he was incarcerated in Arkansas, and it makes a profound statement about his determination to continue as an artist during this period.

Everything in the painting—palette, easel, canvases, beret—proclaims his identity as an artist. The context of the camp, so undeniably stated in almost all of his other paintings from this period, is notably absent here. Sugimoto instead paints himself in an artist’s studio, surrounded by the paintings he is most proud of—his body of work from time spent in France. In this, his only wartime self-portrait, Sugimoto presents himself not as an incarcerated man but as a serious artist.

—Kristine Kim, Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 83.

Additionally, Mr. Sugimoto made his identity known throughout the camp by hanging a palette-shaped sign above the door to his barracks with the title “Artist” painted on it.

There was a sense of enthusiasm and purpose to his work, which spanned most of the twentieth century. To see him, frail yet energized, standing before the easel with palette in hand, applying sure brushstrokes to canvas, is a cherished image. My father, even in his last years, told me that to be able to paint “even for fifteen minutes makes me feel alive.”

—Madeleine Sugimoto, daughter of Henry Sugimoto

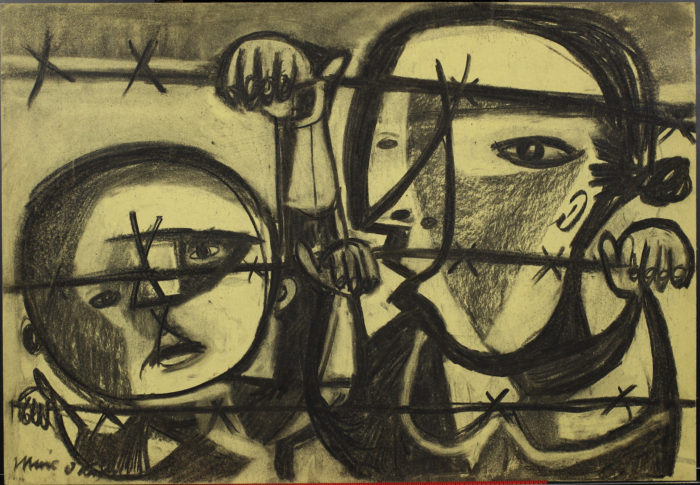

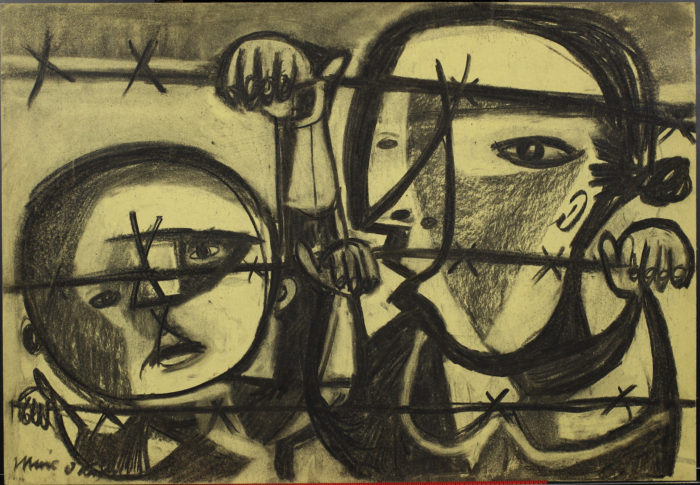

Miné Okubo, Untitled, n.d., charcoal on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What do you see depicted in this charcoal drawing by Miné Okubo?

- Based on body language and facial expressions, what can you infer about these figures?

- What emotions are evoked by this drawing?

Miné Okubo is a Japanese American artist best known for her black and white ink drawings, though this sketch is done in charcoal. As you view more of her works on this website, consider how her artistic tools change the mood of her drawings and why she may have chosen to do this particular scene in charcoal rather than ink.

- How is this sketch different from or similar to the rest of her work?

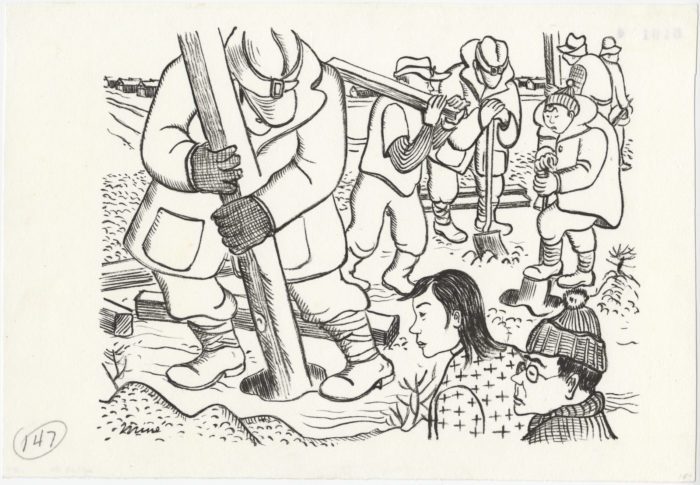

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Fence and watchtower construction, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.154)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a drawing of the Topaz concentration camp by Miné Okubo. She documented her personal story as a Topaz inmate in great detail through her drawings and paintings. Many of her drawings were published in an autobiographical book titled Citizen 13660. In this book, Okubo provided descriptions to accompany each image. Here’s what she wrote about this image:

Fence posts and watch towers were now constructed around the camp by the evacuees to fence themselves in.

- What thoughts do you have as you read this description?

- What questions do you have?

- How does this image heighten the sense of injustice in incarcerating people without cause?

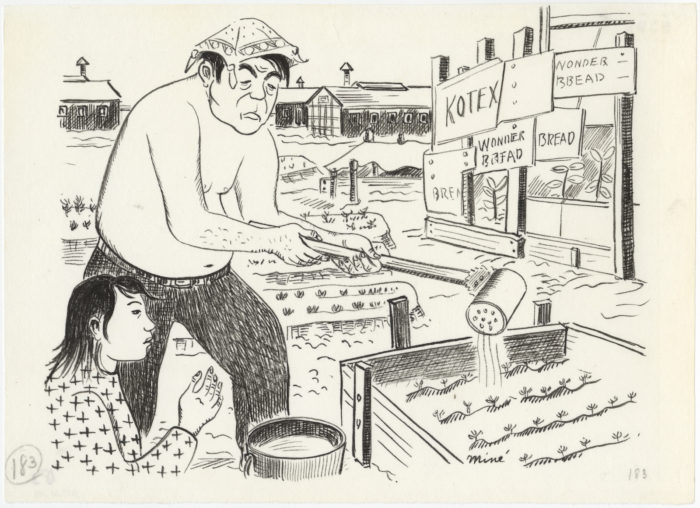

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Victory gardens, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2000.62.190)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is another drawing by Miné Okubo that depicts life at Topaz.

- What do you think the individuals in this drawing are doing?

- Where are they?

- Can you tell what the climate there is like by looking at this drawing?

In Citizen 13660 Okubo wrote the following about this image:

Despite reports that the alkaline soil was not good for agricultural purposes, in the spring practically everyone set up a victory garden. Some of the gardens were organized, but most of them were set up anywhere and any way. Makeshift screens were fashioned out of precious cardboard boxes, cartons, and scraps of lumber to protect the plants from the whipping dust storms.

Victory gardens were planted during wartime to help prevent a food shortage by reducing the demands on the country’s food supply. Eating homegrown produce was also important because the trains and trucks were needed to transport soldiers and weapons for the war. To eat food grown in your garden was a display of patriotism and a way for people to contribute to the war effort. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a big supporter of victory gardens and planted one at the White House.

It is interesting to consider that Japanese Americans incarcerated in camps participated in such a patriotic act during a time when they were not being treated fairly as Americans.

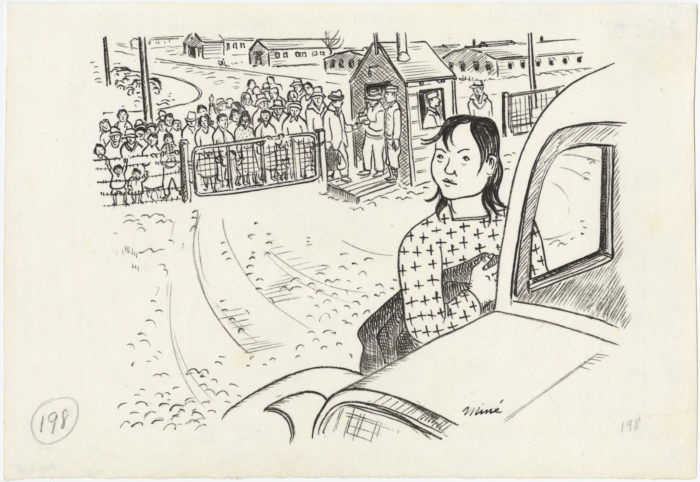

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Boarding the bus to leave camp, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–1944), n.d., ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.205)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.The last image in Okubo’s Citizen 13660 book is this one.

- How would you describe what is depicted in this drawing?

- What evidence do you see to support your description?

- The woman in the foreground is the artist, Miné Okubo. How would you describe her facial expression?

- What thoughts might be going through her mind at this moment?

This is what Okubo wrote about this image:

I looked at the crowd at the gate. Only the very old or very young were left. Here I was, alone, with no family responsibilities, and yet fear had chained me to the camp. I thought, “My God! How do they expect those poor people to leave the one place they can call home?” I swallowed a lump in my throat as I waved good-by to them. I entered the bus. As soon as all the passengers had been accounted for, we were on our way. I relived momentarily the sorrows and the joys of my whole evacuation experience, until the barracks faded away into the distance. There was only the desert now. My thoughts shifted from the past to the future.

Miné Okubo, Untitled, n.d., charcoal on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.5)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In the preface to the 1983 edition of her book Citizen 13660, Okubo wrote:

I was an American citizen, and because of the injustices and contradictions nothing made much sense, making things comical in spite of the misery.

- In what ways do you see this sentiment reflected in her drawings?

Okubo also wrote:

I am often asked, why am I not bitter and could this happen again? I am a realist with a creative mind, interested in people, so my thoughts are constructive. I am not bitter. I hope that things can be learned from this tragic episode, for I believe it could happen again.

—Miné Okubo, preface to the 1983 edition of Citizen 13660

- If you experienced what Okubo experienced by being incarcerated, and witnessed all that she did, do you think you would have feelings of bitterness? Why or why not?

- Do you believe that the incarceration of a group of people could happen again in the United States?

- Why do you think this could or could not happen?

- Does Okubo’s attitude provide any reassurance that injustices can be remedied even if not eliminated?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (2003.294.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What is this a picture of?

- What is it made out of?

- Does it look handmade or store-bought?

- What tells you that?

Read this quotation by Frank S. Emi, the maker of the chest of drawers.

- What does this quotation tell you about Mr. Emi?

- What does it tell you about the conditions at Heart Mountain?

- What does it tell you about the resources available to those incarcerated at Heart Mountain?

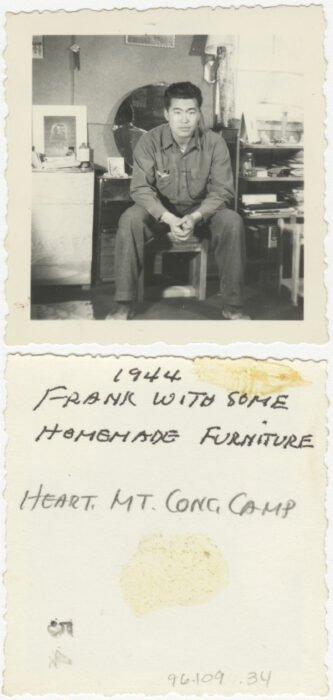

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (96.109.34)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a photograph of Mr. Emi with the vanity he described as his “pride and joy.” The back of the photograph indicates the furniture pictured was made at Heart Mountain concentration camp.

- How would you describe his expression?

- What else do you see in this photograph?

- Without the inscription on the back, would you know where this photograph was taken?

Estelle Ishigo, Untitled (Sept 26-42. Wood for tables and chairs. Japanese Relocation Center. Heart Mt., Wyo.), 1942, watercolor on paper, Japanese American National Museum (94.195.30)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What do you see in this image?

- Where was this image painted?

- What are the people doing?

- What evidence can you find that tells you what is happening in this painting?

This is a watercolor painting by a Caucasian woman named Estelle Ishigo. Estelle lived at Heart Mountain along with her husband, Arthur. While there, she drew and painted many of her experiences, giving us a view into daily life at the camp.

Japanese American families were removed from their homes and permitted to bring only what they could carry. Despite this, there were some intangible things that could not be taken away from the Japanese Americans.

- Which ones are depicted in this painting?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (2003.294.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This simple chest of drawers tells so much about its maker and the conditions under which it was made. When individuals were taken from their homes, they were told they could bring only what they could carry, and this meant they could not take any large furnishings. Upon arriving at the barracks—their new, hastily-constructed homes—the families found that the spaces were small, uncomfortable, impersonal, and unfurnished.

Under these conditions, individuals began to settle in and rebuild the comforts of home inside the concentration camps using the materials available to them. This sense of perseverance and craftsmanship reflects the Japanese Americans’ dignity and desire to make the best life for themselves, their families, and their community even in these conditions of unjust imprisonment.

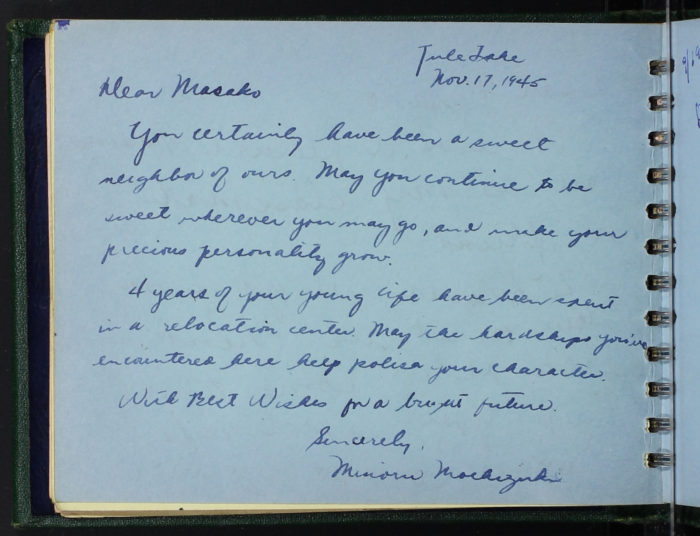

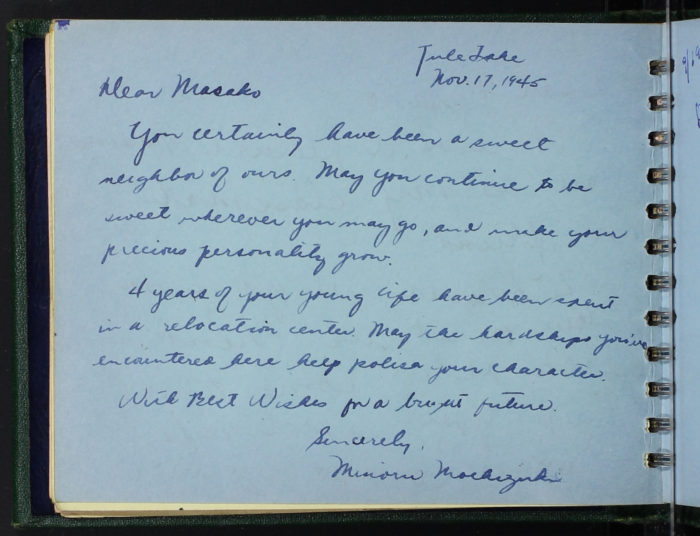

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.9)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a page from an autograph book belonging to Masako Murakami (née Iwawaki). As you read this entry, ask yourself:

- Where was this written?

- When was it written?

- To whom was it written?

- By whom was it written?

- What do you know about Masako and Minoru by reading this text?

Japanese American National Museum, Gifts of Masako Iwawaki Koga (2003.37.2, 2003.37.6, 2003.37.11, 96.14.3)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.

The wooden pins pictured were made by Masako’s grandmother Tsuya Mukai while incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Tsuya sent them to Tule Lake, California, where her daughter Toshiko and granddaughters Yaeko and Masako were living.

- What do you learn about Tsuya Mukai by looking at these pins?

The tiny decorative geta (Japanese footwear) were made by Masako while incarcerated at Tule Lake. Notice how detailed they are.

- What conclusions can you draw about Masako by looking at these?

- Why do you think Masako made these?

Many crafts emerged from America’s concentration camps as Japanese American inmates found ways to expend their creative energy. The fact of their barbed-wire confinement did little to suppress the Japanese Americans’ desire to bring some normalcy to their mundane camp lives.

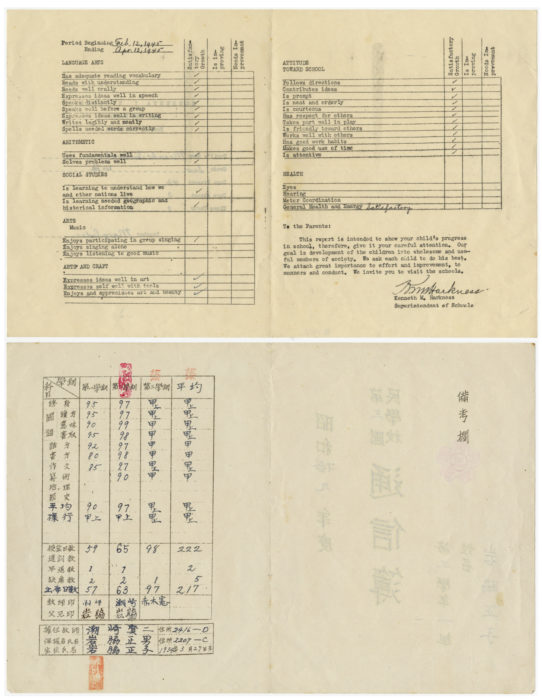

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.6, 96.14.7)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.These are two report cards belonging to 11-year-old Masako. They are from her time spent at Tule Lake Segregation Center.

- What do you notice about these cards?

Masako attended school in English, studying subjects such as language arts, arithmetic, social studies, and arts. She also studied Japanese, which is why one of these report cards is in Japanese.

- Based on the evidence in these two documents, what can you learn about Masako?

- Based on the evidence in these two documents, what can you learn about the community at Tule Lake?

- Why would it be important for Masako, a young American of Japanese ancestry, to also study Japanese?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.10)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- Where do you think this photograph was taken?

- Who do you think is depicted in this photograph?

- What visual evidence leads you to these conclusions?

Pictured at the far right is Masako Murakami. She was about 11 years old when this photograph was taken at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California. She is shown here with friends who lived on the same block as she did.

- What expressions do you see on the faces of these individuals?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Masako Iwawaki Koga (96.14.9)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Read this note once again. Masako was born in 1934 and received this letter in 1945 as she was leaving Tule Lake. If Masako spent four years incarcerated, as is indicated in this note, she would have been incarcerated in America’s concentration camps from approximately age 7 to 11. Now Imagine yourself at that age.

- How would you spend your time behind barbed wire?

- How would you build community?

- How would you preserve your culture?

Masako attended school, did crafts, and made many friends, as evidenced by the autographs in her book. It is clear that she was a young person who made the best of her situation.

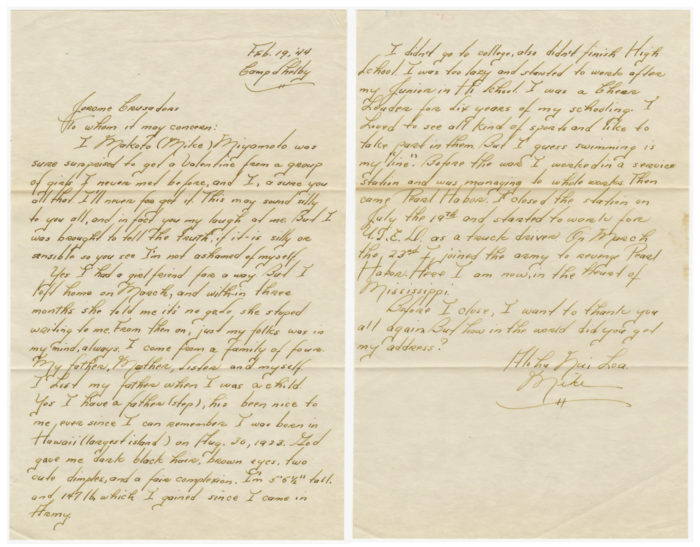

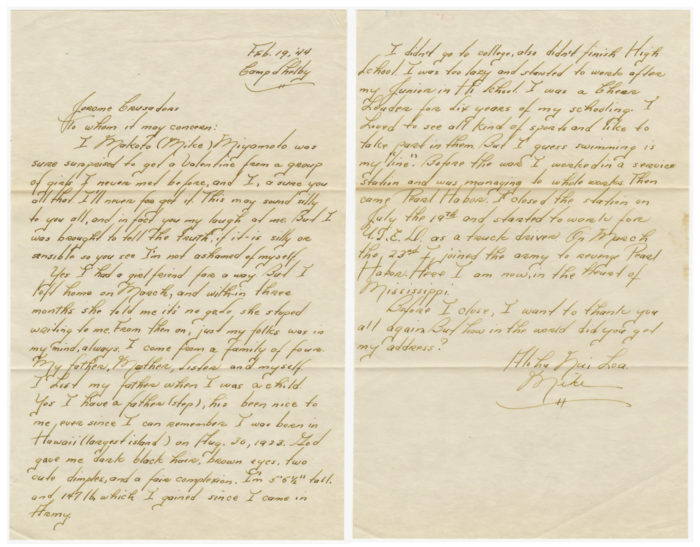

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Take a look at this letter from 1944.

- To whom is it addressed?

- Who sent it?

- What type of information is being shared?

- Do you think the writer knows the recipients?

While incarcerated in Jerome, Arkansas, a small group of five Sunday school students and their teacher, Mary Nakahara (who later became notable civil-rights activist Yuri Kochiyama), decided to start writing to Japanese Americans serving in the military. This effort grew as other students and parents joined in. They wrote to soldiers whose names they gathered by asking around in their community to find those with family members serving in the military. The letter-writers called themselves the Crusaders.

This page is taken from a scrapbook of letters and cards exchanged between the soldiers and the Crusaders. It was compiled and saved by Rinko Shimasaki, one of the high school students who corresponded with the soldiers.

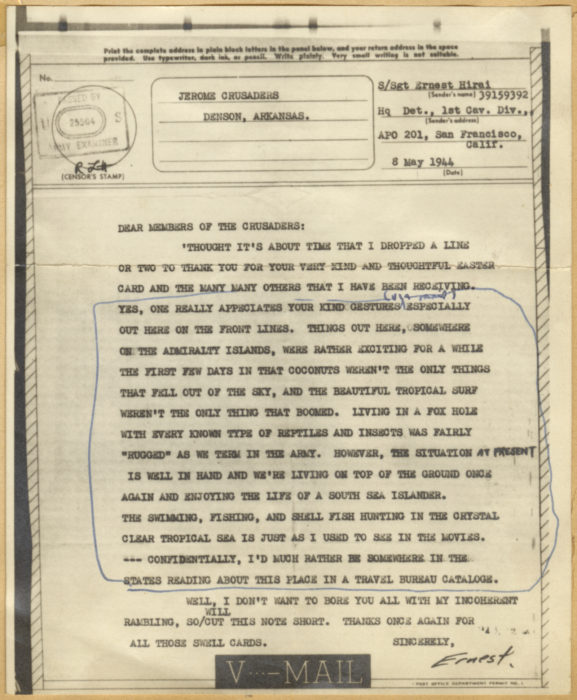

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a letter to the Jerome Crusaders from Sgt. Ernest Hirai.

- What is the tone of this letter?

- By reading this letter, what can you gather about the conditions in which Sgt. Hirai is living?

- Look at the designs on the paper on which the letter is typed. What details do you notice?

- Do you see the censor’s stamp? Why would this letter need to be censored?

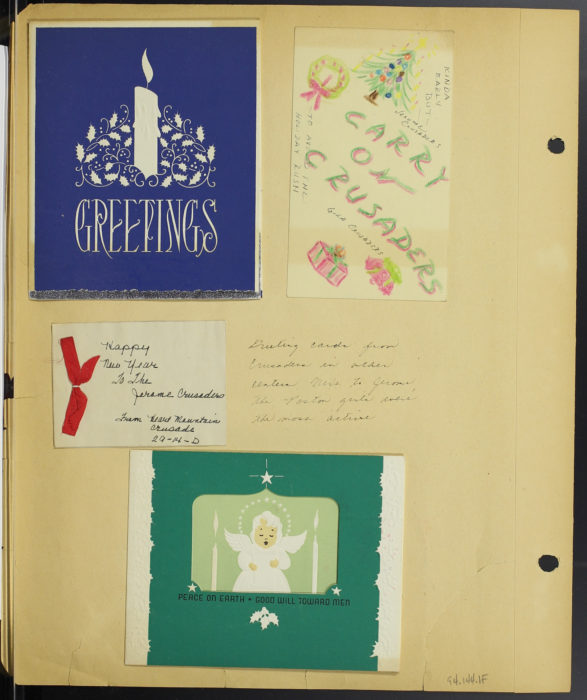

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (96.144.1F)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a page from the Crusaders’ scrapbook. Look closely at these greetings.

- To whom are they addressed?

- Who sent them?

The Crusaders expanded beyond Jerome with members in other camps as well.

- What evidence of membership in other camps can you see on this page of greeting cards?

The Crusaders were a strong network of letter writers. Despite the distance between the camps, the Crusaders shared a desire to support the soldiers in their communities and show they cared.

Yuri Kochiyama video interview (June 16, 2003), Japanese American National Museum, DiscoverNikkei.org

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In this video clip, Yuri Kochiyama talks about how a project started by a small group of young students grew rapidly to include many.

- What do you think compelled so many people to become involved?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Yuri Kochiyama (94.144.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.By writing these letters, young children and teenagers expressed support for those serving their country. Since so many had brothers, fathers, uncles, and other relatives serving in the military, others in the community got involved as well.

Mrs. Kochiyama recalls that her mother became very involved in letter writing just after her father passed away, when her mother was very lonely. Writing letters and notes to the soldiers created a sense of community among those in the camps.

As we read the correspondence, it is evident that these letters meant a great deal to the soldiers. They became a link to the community when the soldiers were far from home.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look closely at this photograph and the handwritten text at the bottom.

- What do you see?

- What evidence in the photograph gives you clues about where this photograph may have been taken?

- Does this photograph convey to you that the New Year holiday is coming?

The individuals in this photograph are making mochi while incarcerated at Gila River, Arizona. Mochi is a Japanese rice cake made by steaming and pounding rice and then forming it into small round shapes, as seen in this photograph. Sticky in texture, it is a very traditional food made and eaten by Japanese families during the New Year holiday. Often families have large gatherings and work together all day making mochi. It is a custom that continues today in many Japanese and Japanese American families.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look closely at this photograph.

- What do you see?

- Do you have any guesses about what is happening in this photograph?

- Is there anything you wonder about what is happening in this photograph?

This photograph was taken at Gila River and shows the part of the mochi-making process in which the rice is steamed in preparation for pounding.

- What do you notice about the people in this photograph?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.2)

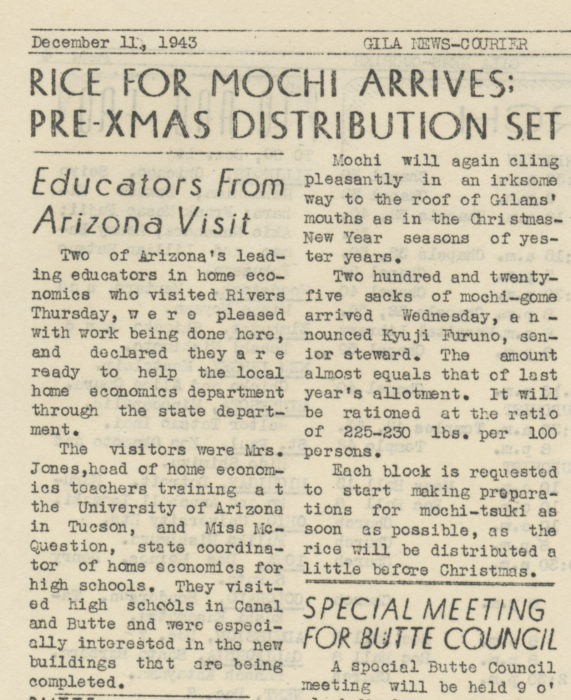

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a page from the Gila News-Courier, the newspaper printed in the Gila River Concentration Camp in Arizona. Read the article titled “Rice for Mochi Arrives: Pre-Xmas Distribution Set” and consider the importance of this event to the incarcerated community at Gila River.

Here are some definitions that may be helpful as you read the article:

mochi-gome: sweet rice used to make mochi

mochi-tsuki: the making of mochi

Gilans: individuals living at Gila River

Mochi is associated with a happy time of year and mochi-making is an activity that brings Japanese American families and their communities together.

As you read the first sentence, ask yourself what types of feelings you think the Japanese and Japanese Americans associate with mochi.

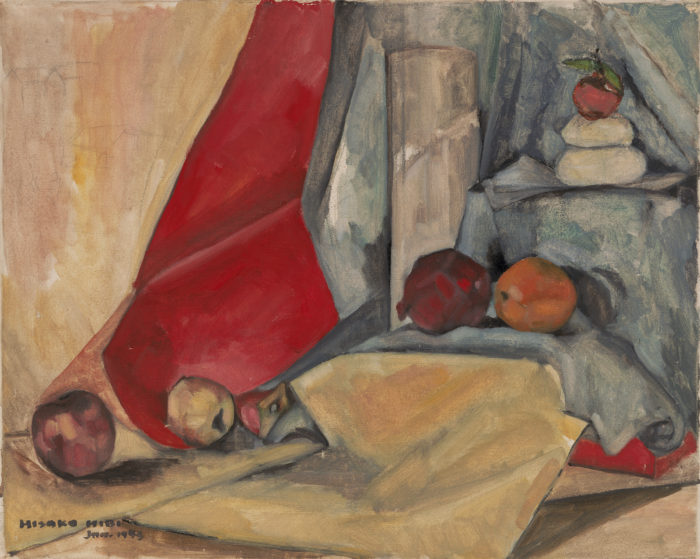

Hisako Hibi, Untitled (New Year’s Mochi), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Ibuki Hibi Lee (99.63.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- Can you spot the mochi in this painting?

- What else do you see depicted?

- What would you say is the mood of this painting?

This painting was made by an artist named Hisako Hibi. During World War II, she was incarcerated in a concentration camp in Topaz, Utah, and it was there that she painted this image. The formation of two stacked mochi topped with a small citrus is called an okasane. It symbolizes hope for health and prosperity and is often displayed in homes during the New Year season.

- Why might painting a picture of an okasane be important to Hibi while she is in camp?

On the back of this painting is an inscription that reads:

Hisako Hibi. Jan 1943 at Topaz. Japanese without mochi (pounded sweet rice) is no New Year! It was very sad oshogatsu (New Year). So, I painted okazari mochi in the internment camp.

- Now that you know what is written on the back, does it change the mood of this painting for you? If so, how?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of George Teruo Esaki (96.25.8)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.As evidenced by the artifacts seen here, mochi and the communal process of making it represent very strong cultural traditions.

This is one aspect of their culture that Japanese American inmates, despite the harsh conditions in which they lived, could not give up. These artifacts show how traditions expressed in actions and art help to maintain community and culture.

- Which aspects of your family’s or community’s culture do you maintain?

- In what ways do you achieve this?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Susumu Ito (94.306.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This object is called a senninbari.

- How would you describe the senninbari?

- What materials is it made of?

- Why do you think there is a tiger depicted on it?

- What else do you notice?

- What might it have been used for?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Susumu Ito (94.306)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Born in California in 1919 to a family of immigrant tenant farmers, Sus Ito was drafted into the US Army in February 1941. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he was switched to civilian duty while his family was sent to live at Rohwer concentration camp in Arkansas. In the spring of 1943, he was selected to join the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 522nd Field Artillery Battalion. Ito went on to serve in all of the 442nd’s campaigns in Italy, France, and Germany, eventually rising to the rank of lieutenant. His tour of duty included high-profile historical events such as the rescue of the Lost Battalion and the liberation of a subcamp of Dachau.

During his time in Europe, Ito kept three things with him: a small Bible, a senninbari (Japanese 1000-stitch cloth belt traditionally given to soldiers who are going to war) made by his mother at Rohwer, and a 35mm Agfa camera. He took thousands of photographs documenting his life in the military and went to great lengths to preserve the negatives, even having some of them developed at villages he was stationed at along the way. Ito’s vast archive of images taken while on duty during World War II gives a rare and breathtaking look at daily life within the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion of the celebrated all-Japanese American 442nd RCT.

Susumu Ito video interview (July 8, 2015), Japanese American National Museum

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In this video clip, Dr. Ito says he didn’t wear his senninbari or show it to his fellow soldiers.

- Why do you think this is?

Henry Sugimoto, Untitled (In Camp Jerome), 1943, oil on canvas, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.9)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This painting shows a senninbari as depicted by artist Henry Sugimoto.

- Who might the person holding the senninbari be?

- Who might the other individual in the image be?

- What symbols are evident in this image?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Susumu Ito (94.306.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.A senninbari (Japanese for “1000-person stitches”) is a strip of white cloth with 1000 red stitches, each made by a different woman, which is given to soldiers going off to war. It originated in Imperial Japan and served as an amulet for a safe return home.

Senninbaris are often made by mothers or wives, with a community of other women, to give protection to husbands and sons departing for war. Dr. Ito’s mother organized the women in Rohwer to contribute by each putting in a stitch; his cousin Emiko put the last stitch into this senninbari.

I so highly valued the senninbari that it was the item that bound me to my mother and furthermore made me feel that I had no fear that I might not survive the many combat experiences and come home intact. However, being an item that Japanese soldiers carried into combat, I did not tell anyone, even my closest buddy, that I had this item and kept it a secret through the War.

I treasured it. My mother used to tell me about senninbaris as a child. She sent it to me. I carried it in my pocket. I had a close attachment to it, and to my mother because she made it. I’d like to think that my senninbari helped get me back safely.

—Sus Ito, email to Lily Anne Yumi Welty Tamai, February 20, 2015

- How does the story of Dr. Ito’s senninbari reflect his identity as a Japanese American soldier and the anxiety of being Japanese American at that time?

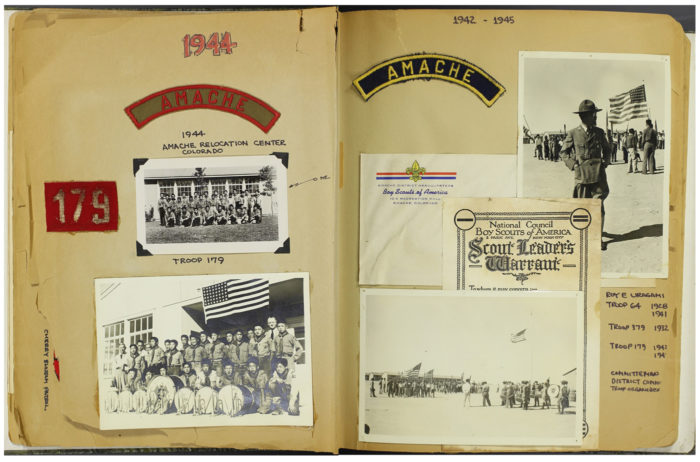

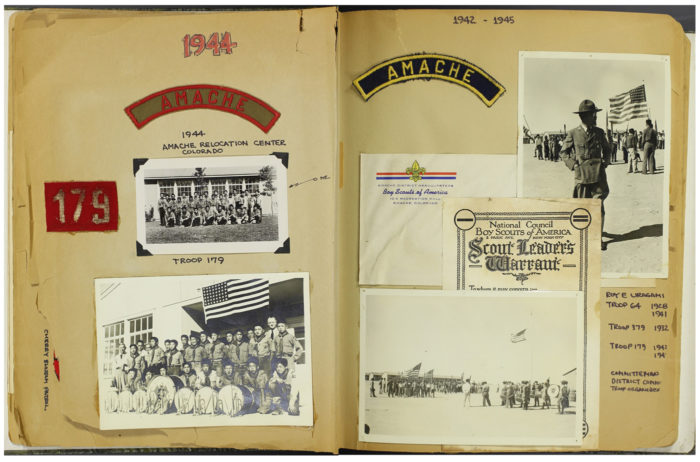

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (2003.86.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.These are two pages from a 73-page scrapbook documenting three generations of boy scouting in a Japanese American family. The scrapbook was made by Bob Uragami, whose father, Roy, was the first to become involved with scouting; Roy was followed by Bob, and later Bob’s son, Tim.

Look closely at these two pages.

- What do you recognize?

- What things do you wonder about?

- Where were these items used and when were these photographs taken?

- As you look at the photographs, what stands out to you?

- Why do you think Bob decided to include these specific photographs and mementos in his scrapbook?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (2003.86.1)

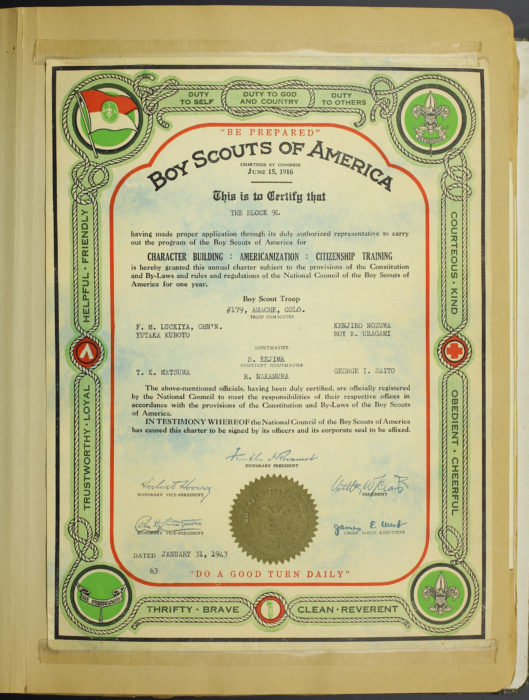

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This Boy Scouts of America certificate was given to the Boy Scout troop of Japanese Americans incarcerated at Amache, Colorado. Look closely at the text and designs on this certificate.

- How would you describe the overall tone of this certificate?

- Which words stand out to you?

- How would you have felt if you received this certificate from the Boy Scouts of America while you were imprisoned by the US government?

- How might words such as “duty to country” and “Americanization” feel different to the members of this troop under the conditions in which they lived?

Bob Uragami video interview, Japanese American National Museum

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In this video, Bob Uragami speaks about the drum that was used by his Boy Scout troop while incarcerated at Amache. The drum can also be seen in one of the images in the scrapbook. As you watch this video, consider what Mr. Uragami says about the flags depicted on the drum.

When he refers to the “meatball,” he is using a nickname for the Japanese flag, which has one large circle on it.

- How does the story about the flags reflect the identity of this group of Boy Scouts?

- How does the story about the burial suit reflect the identity of Mr. Uragami’s father?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (99.2.8B)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What do you see depicted in this image?

- Who do you think the man in the foreground is?

- Where do you think this photograph was taken?

- What evidence in the photograph helps you draw these conclusions?

This photograph was taken at Amache Concentration Camp. Roy Uragami, the father of Bob Uragami, is pictured in his uniform in the foreground.

- How would you describe Roy Uragami’s expression?

- What thoughts might be going through his head at this moment?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Robert and Rumi Uragami (2003.86.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Objects can tell us a lot about the people who use them. The scrapbook, the Boy Scouts of America certificate, the drum, and the photograph of Roy Uragami in uniform all convey a sense of patriotism.

Bob Uragami kept memorabilia and photographs from his time as a Boy Scout in Amache. He was a young American and proud to belong to the Boy Scouts of America even at a time when the United States, by incarcerating Japanese Americans, was telling him that he did not belong. The fact that Mr. Uragami chose to keep these things shows that the items reflect an important part of his identity—his past as an American kid who participated in ordinary American activities during a very unordinary time. Through these artifacts, we see how a bicultural Japanese American identity was created within the concentration camp.

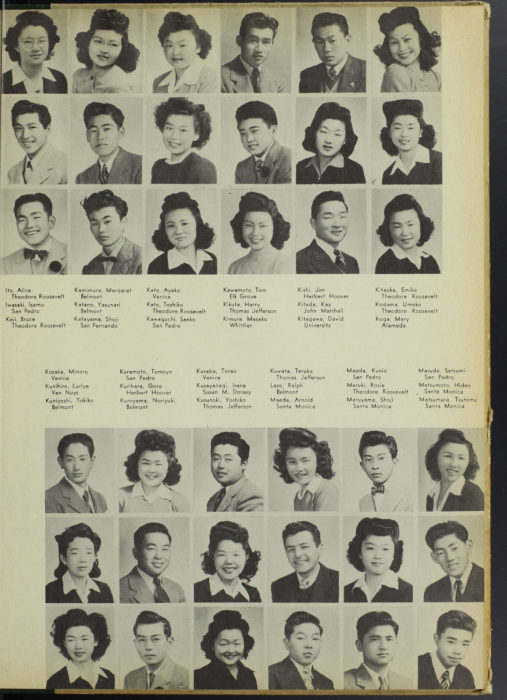

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

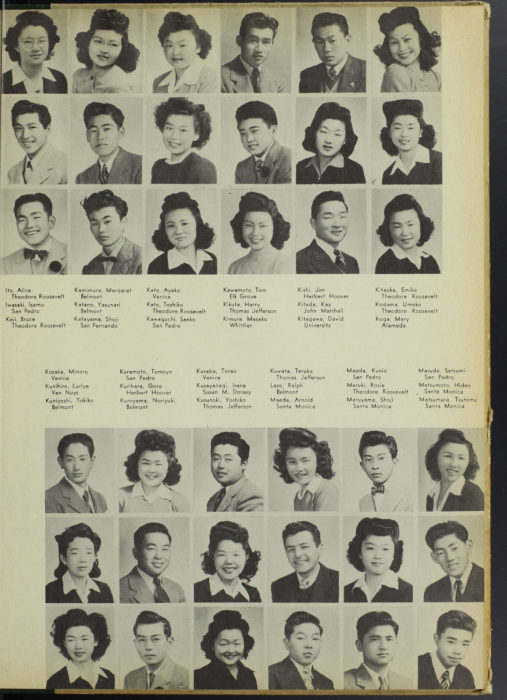

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a page from the 1944 Manzanar High School yearbook. Look carefully at these faces and names.

- What do you notice?

As one might expect, almost all of the students pictured in the yearbook are Japanese American. There is one student, however, who is not. Find the photograph of Ralph Lazo. Lazo is of Mexican and Irish descent.

- Why do you think he is pictured in this yearbook from Manzanar Concentration Camp?

- What events might have led to him living in Manzanar?

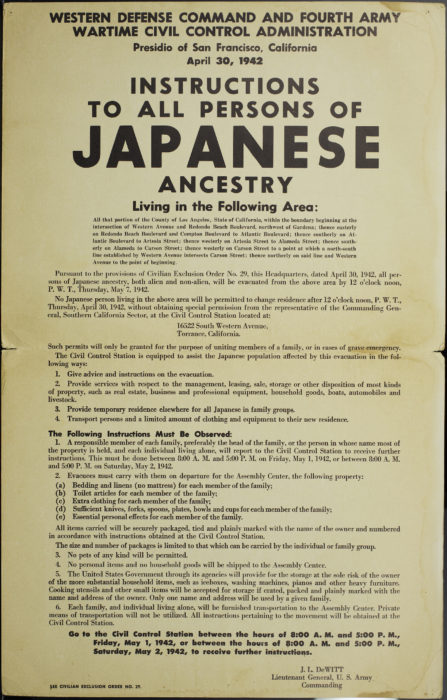

“Public Proclamation No. 29” (April 30, 1942), Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.13)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Read the text of this document carefully. This is a Civilian Exclusion Order. In 1942, these posters were placed in public areas all along the West Coast of the United States.

- To whom are these instructions directed?

- If you were a person of Japanese ancestry, how would you feel as you read these posters?

- If your best friend was a person of Japanese ancestry, how would you feel as you read these posters?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Although Ralph Lazo was not Japanese American, many of his friends at Belmont High School in Los Angeles were. When the Civilian Exclusion Order called for all persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast to be incarcerated in concentration camps, Ralph witnessed many of his good friends forcibly removed from their homes and sent to camp. He considered his Japanese American friends to be his equals. Realizing the incarceration was unjust and wishing to support his friends, Ralph decided he would go to camp as well. He ended up living at Manzanar and going to high school there.

Take a look at this photograph from the Manzanar High School yearbook.

- Can you find Ralph Lazo?

- Does he stand out from the others in a drastic way?

- How would you describe his mood?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Hannah Tomiko Holmes (94.181.134)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This snapshot was taken during a press conference for the National Council for Japanese American Redress, many years after the teenaged Ralph Lazo joined his friends at Manzanar. The council was formed in 1979 to obtain restitution for Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II. In this photograph, Lazo is shown on the left.

- By looking at this photograph taken decades after World War II, what do you learn about Ralph Lazo as an adult?

Lazo’s presence in this photograph shows how even decades after World War II he continued to support his Japanese American friends and the Japanese American community.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Helen Ely Brill (95.93.2)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.As a teenager, Ralph Lazo was angered by the incarceration of his friends and decided to do something about it. Though a handful of inmates entered the War Relocation Authority camps voluntarily, because they were not Japanese American, Ralph was the only among them who was not married to a Japanese American. Taking action in a big way to express dissent against the injustice of his friends’ imprisonment, Ralph’s demonstration of support made a lasting impact. While in camp, he was a well-liked leader and was involved in many activities, even becoming class president.

- If you were in Ralph’s position, how would you respond to the incarceration of your friends?

- If you were in the position of his friends, how would you feel about Ralph’s presence in the camp?

- What insights can you gather from Ralph’s story about various ways of expressing dissent?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.2A)

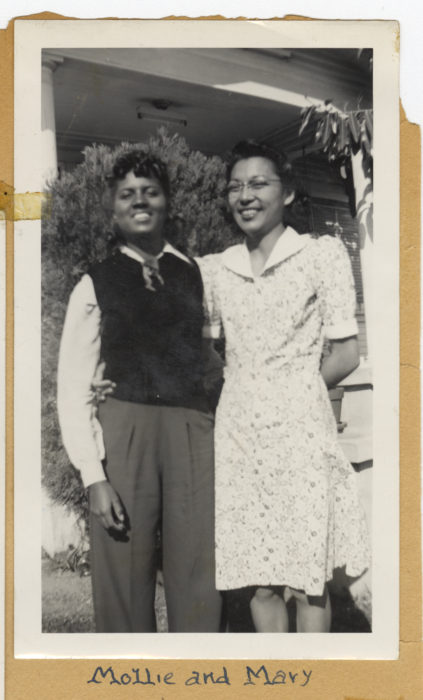

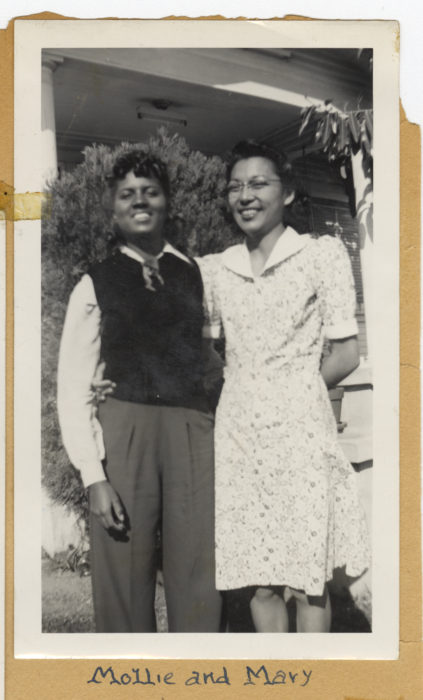

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- As you look at this photograph, what do you notice?

- What are some things that give you a sense of the time period?

- What are the names of these two individuals?

- Do you have any guesses about who they are and what their relationship is to one another?

- How would you describe the mood of this photograph?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.5F)

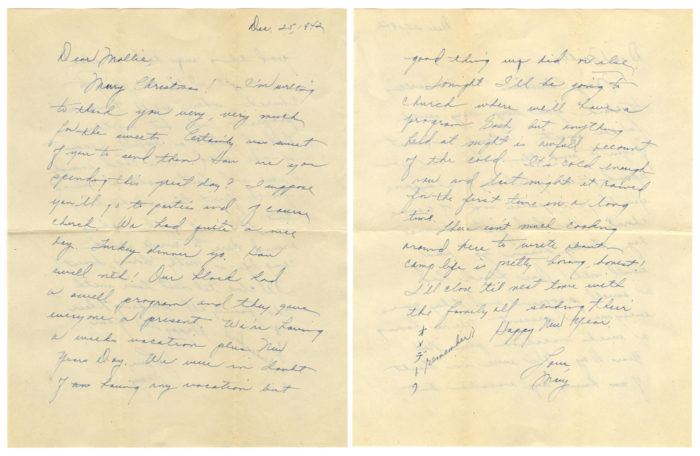

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Carefully read this letter and consider the following questions:

- Who wrote this letter?

- To whom was the letter written?

- What information can you gather about who Mollie is? Where is she?

- What information can you gather about who Mary is? Where is she?

- What are some of the topics written about in this letter?

- Based on the content of this letter, what kind of camp is Mary referring to?

Mollie Wilson lived in Los Angeles and attended Roosevelt High School. Many of her Japanese American friends were forced to move during World War II. She would often write to her incarcerated friends, such as Mary Murakami.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.5B)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Letters provide a great window into history. Even from an envelope alone, there is much information to be gathered. This is the envelope for a letter from Mary to Mollie.

Look closely at the envelope.

- What do you notice?

- Based on the return address and cancellation stamp, can you tell where Mary was living when she sent this letter?

- Why do you think one address is crossed out and replaced by another?

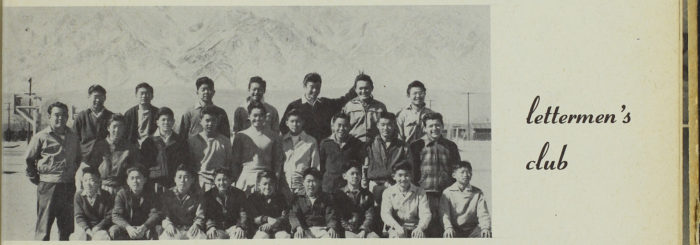

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.24)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a photograph of Sandie Saito. Like Mary, she was a friend of Mollie’s from Roosevelt High School. Sandie is pictured here in a Roosevelt letterman sweater while incarcerated at Amache, Colorado. Sandie sent this photo to Mollie from Amache. In the corner she wrote, “To Molly, Just, Sandie,” and on the back of the photograph it says, “This picture was taken way at the west end of the football field.”

Imagine being a young person who is forced to abruptly migrate to an unknown place, far from everything familiar.

- What people, places, activities, or things would you miss about your daily life?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy (2000.378.2A)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Childhood friends since elementary school, Mollie and Mary grew up together in an area of Los Angeles called Boyle Heights. They were high school students when Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes and communities.

Mollie kept in touch with many of her Japanese American friends during the war by corresponding with them regularly through letters. She shared what was going on in the Boyle Heights neighborhood, and her friends would share details about their lives in the assembly centers and concentration camps. The letters would often include discussions about the weather and living conditions but also gossip about school, boys, movies, and other topics of interest to the teenaged friends.

- Which feelings, thoughts, or memories would letters or photographs like these from a far away friend evoke?

Through the simple act of writing letters and sending gifts, Mollie displayed loyalty to her friends despite the miles between them.

- In what ways is loyalty based on friendship similar or different to loyalty based on a nation or ideas?