Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.49.33)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Read this document closely.

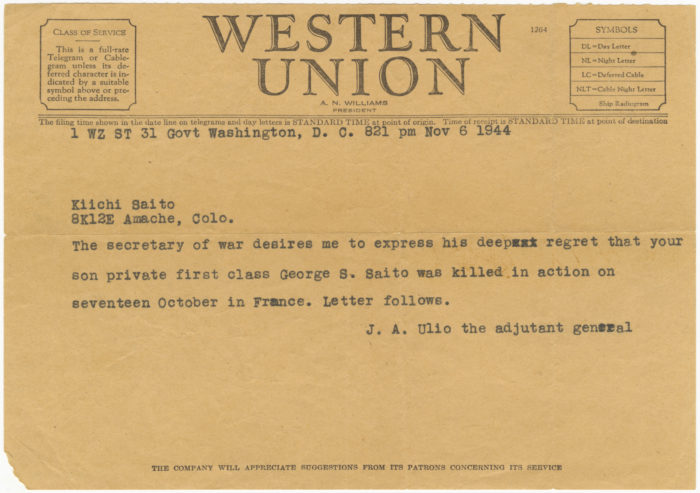

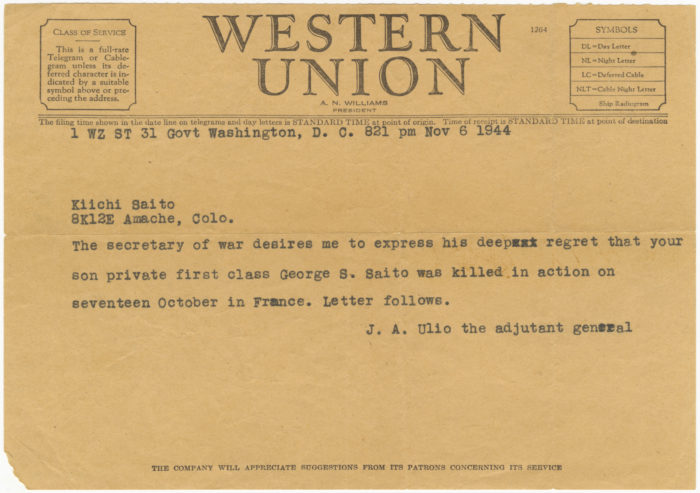

This is a telegram to Kiichi Saito. Three of Mr. Saito’s sons served in the United States Army during World War II including his son George, who is referenced in this telegram.

- Where was Mr. Saito living at the time he received this telegram?

- How would you describe the tone of this message?

- What questions do you have after reading this document?

Mary Saito Tominaga and Kazuo Saito video interview (November 2, 2010), Japanese American National Museum

Click to open full-size image in new tab.

Watch this video of George Saito’s brother Kazuo and sister, Mary.

- Based on what they say about him in this clip, why do you think George decided to join the army?

- What can you gather about George from this clip? What type of person was he?

- Where was the Saito family living when George left to join the army?

- Did you notice the photograph of George and his brothers Calvin and Shozo? How are they all dressed in the photograph?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.49.41)

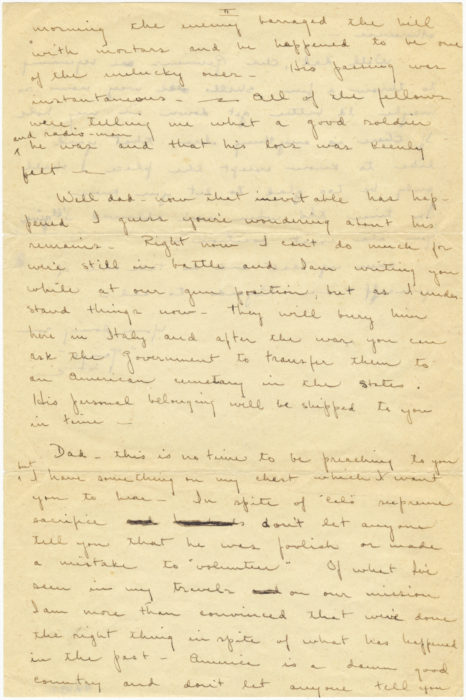

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In 1944, while attacking a hill in Italy, George’s younger brother Calvin, who was also serving in the army, was struck and killed. This is from a letter George sent home to console his grief-stricken father.

Dad—this is no time to be preaching to you but I have something on my chest which I want you to hear In spite of Cal’s supreme sacrifice, don’t let anyone tell you that he was foolish or made a mistake to “volunteer.” Of what I’ve seen in my travels, on our mission, I am more than convinced that we’ve done the right thing in spite of what has happened in the past. America is a damn good country and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

– George Saito, letter to his father, July 11, 1944

- What do you think is the main message George has for his father?

- If you were in George’s position, do you think you would share his sentiments? Why or why not?

- Why do you think George felt it necessary to write these words?

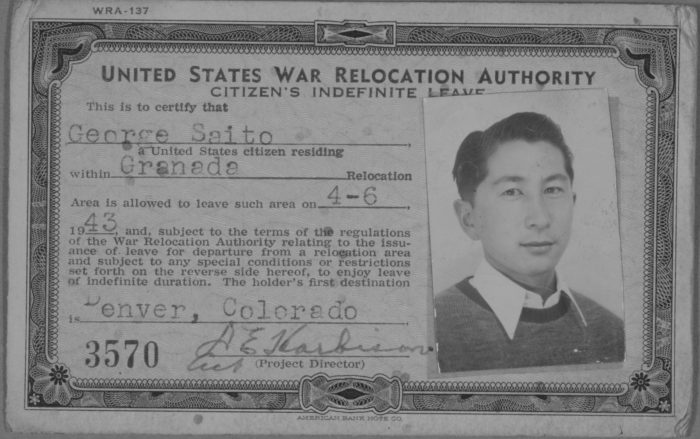

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.6.77)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- Does this document give any clue as to who George Saito is?

- Does he look like a young man or an older man?

- What country is he a citizen of?

- What might prompt a government to monitor its citizens in this way?

- At the time this document was issued, where was George residing?

- Does such a document make you question the rights and limitations of an American citizen?

This document is George’s indefinite leave card, issued by the government as a way to monitor any subversive behavior in its American-born citizens of Japanese ancestry. This card gave George permission to leave Amache concentration camp. Soon after its issuance, George enlisted in the United States Army and served in the segregated 442nd RCT in Europe.

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mary Saito Tominaga (94.49.33)

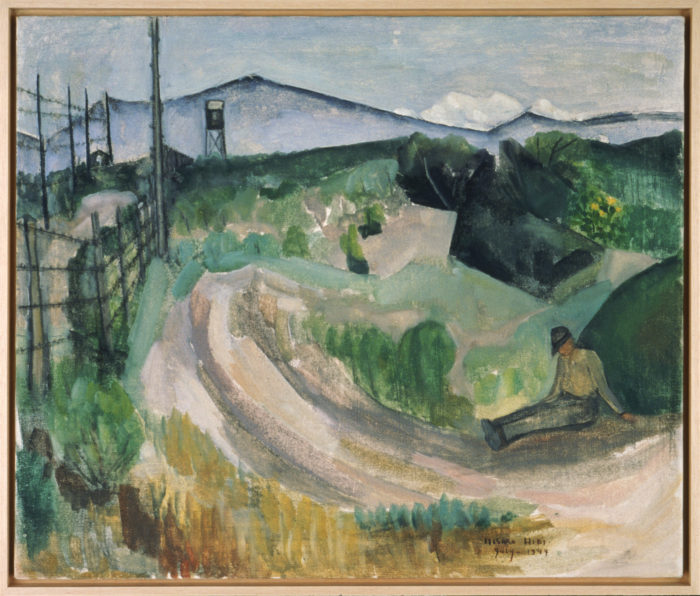

Click to open full-size image in new tab.In 1942, the United States government forced the Saito family to leave their home in Los Angeles, California, where George had a produce market. They were sent to Granada concentration camp, also known as Amache. (One brother, Kazuo, was sent to Heart Mountain because he lived in a different part of Los Angeles than the rest of his family.)

Amache is where the Saito family was living when 25-year-old George volunteered for the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. George hoped that his service would free his family from unjust imprisonment. Together with his younger brothers Shozo and Calvin, George was sent to Europe, where he fought as a loyal American who strongly believed in his country. This sentiment of loyalty was shared by many young Japanese Americans who fought for their country despite its great violation of their civil rights.

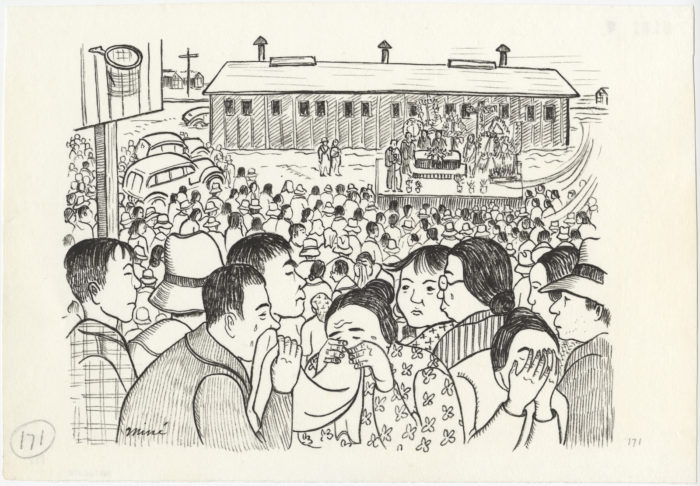

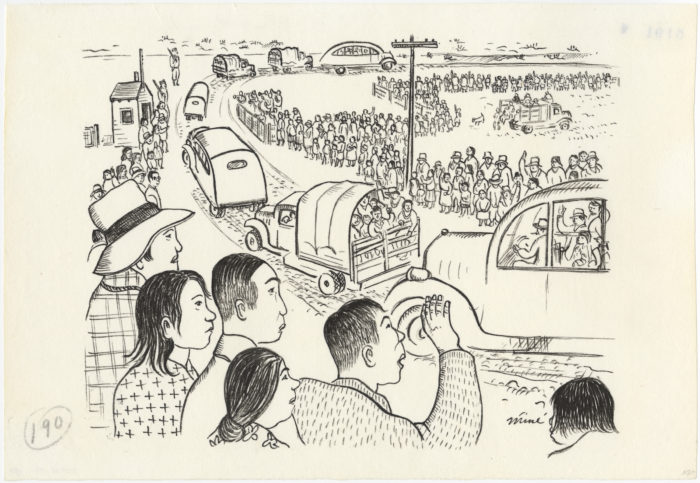

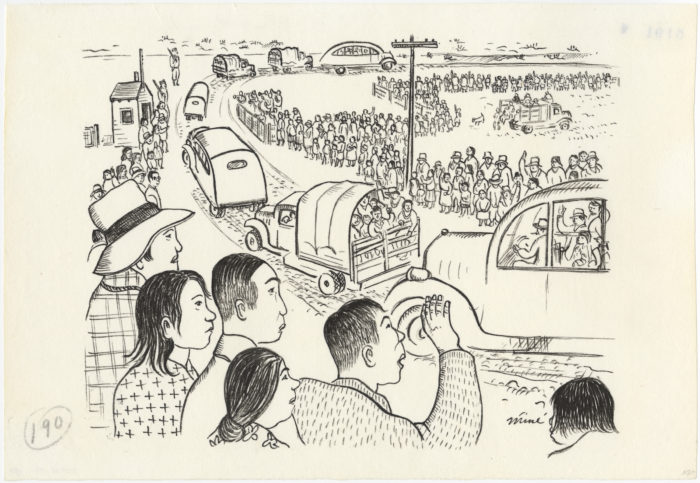

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Departure and segregation of pro-Japanese to Tule Lake, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–44), c. 1942–44, ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.197)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Look carefully at this drawing by Miné Okubo. Examine all the details in the foreground, middleground, and background.

- What is depicted in this drawing?

- Where might all the people in the vehicles be leaving from?

- Where might they be going?

- How would you describe the expressions on the faces you see?

- What questions do you have about this image?

In her book Citizen 13660, originally published in 1946, Ms. Okubo wrote the following about her image:

The program of segregation was now instituted. One of its purposes was to protect loyal Japanese Americans from the continuing threats of pro-Japanese agitators. Tule Lake, one of the ten original centers, was chosen as a segregation center for the disloyal. In the fall of 1943 thirteen hundred Topazians (about one tenth of the total) were sent there. The group included all who had said they wished to return to Japan; the “no, nos,” that is, those who would not change their unsatisfactory answers to the questionnaire when they were given a chance to do so; all who remained under suspicion of disloyalty after investigation by the War Relocation Authority and the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and close relatives who would rather be segregated with their families than separated from them.

Whatever decision was made, families suffered deeply.

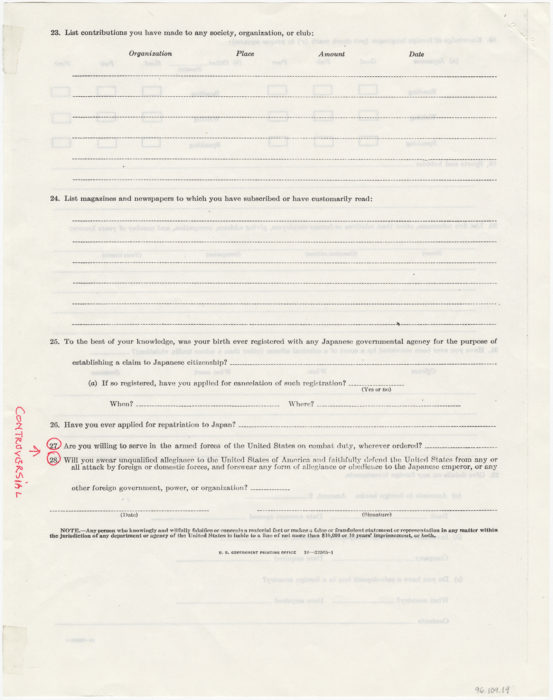

Loyalty questionnaire, 1943, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Frank S. Emi (96.109.19)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is a page of the loyalty questionnaire administered to Japanese Americans while they were imprisoned in concentration camps. Take a look at questions 27 and 28.

Imagine if you were a young American citizen of Japanese descent incarcerated in a concentration camp and presented with these questions.

- How would you respond?

- Why would you respond in this way?

- What questions or concerns would you have?

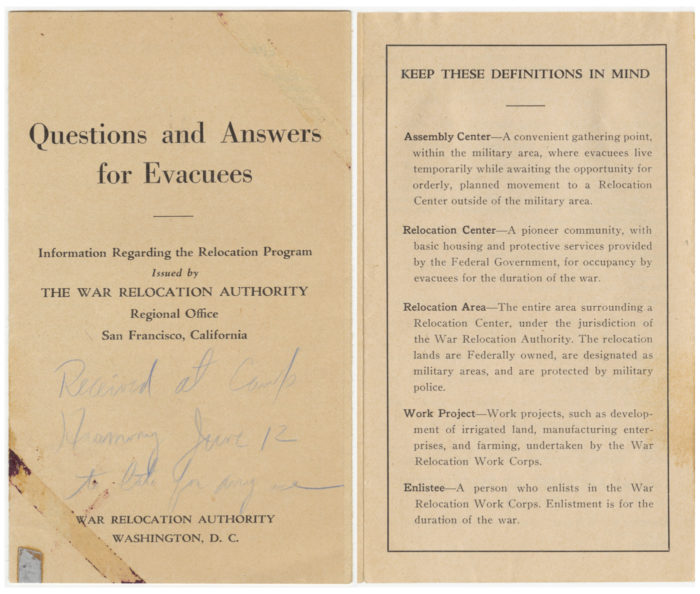

The War Department and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) scored the answers to the loyalty questionnaire by ranking them according to Americanness and Japaneseness. Especially problematic were questions 27 and 28. Question 27 asked if Nisei men were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered and asked everyone else if they would be willing to serve in other ways, such as joining the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Question 27 was an insulting question to some who were angry about being incarcerated. Question 28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. The problem this question posed was that Issei were not allowed to become American citizens—if they forswore allegiance to the Japanese emperor, they would become stateless, without any connection to a government; and the Nisei, who were American citizens, never had any allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

At most of the incarceration camps, Japanese Americans answered “yes” to both questions 27 and 28. However, many were uncomfortable making this agreement to serve in the military at the same time that the US government was suspending their constitutional rights. For this reason, there were some who answered “no” to both questions. Labeled as disloyal, they were sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center.

LIFE Magazine Vol. 16, No. 12 (March 20, 1944), Japanese American National Museum, Gift in Memory of Hugo W. Wolter (97.329.96)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Without reading the caption, look closely and answer the following questions:

- How would you describe the individuals in this photograph?

- What things do you see in the space they are in?

- Can you guess where this photograph was taken?

Now read the caption of the photograph.

- Does any of the information surprise you? If so, which information and why?

- How does the caption contrast with the image?

- What message do you think the photographer is trying to convey with this image?

Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Charles and Lois Ferguson (93.3.1)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.- What would you say is the tone of this speech?

- What are the main messages conveyed?

- What can you conclude about Mr. Kurihara based on his words?

- To whom do you think this speech is being directed?

This is an excerpt from a speech written by Joe Kurihara while he was an inmate at Manzanar concentration camp. Mr. Kurihara was born in Hawai‘i and served in the United States Army during World War I. During his incarceration, Mr. Kurihara was an outspoken dissident leader against the US government’s unjust imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

Due to his actions as an agitator, Mr. Kurihara was transferred from Manzanar to Tule Lake, the segregated center for Japanese Americans who were alleged to be disloyal.

Mr. Kurihara’s anger eventually led him to renounce his US citizenship and go to Japan, where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Departure and segregation of pro-Japanese to Tule Lake, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942–44), c. 1942–44, ink on paper. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of the Miné Okubo Estate (2007.62.197)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.As evidenced by the artifacts here, the story of Tule Lake is not a simple one. In July of 1943, Tule Lake became a segregated camp where only Japanese Americans who were alleged to be disloyal based on their answers to the loyalty questionnaire were sent. Among those designated disloyal were United States citizens, including young children; families who had sons fighting overseas in the US military; World War I veterans; and others.

During this time, Japanese Americans were faced with impossible decisions.

Imagine you are a young person incarcerated in Tule Lake. You are a United States citizen because you were born here; however, your government has imprisoned you and labeled you as disloyal. You are of Japanese ancestry, but maybe you’ve never even been to Japan.

- Would you feel inclined to reject your American citizenship?

- Would going to Japan be a viable option for you?

- If asked to choose between these two countries, would you be able to understand the consequences and make that choice?

- If your family members made the decision to give up their American citizenship and move to Japan, would you go with them or would you choose to remain in the United States?

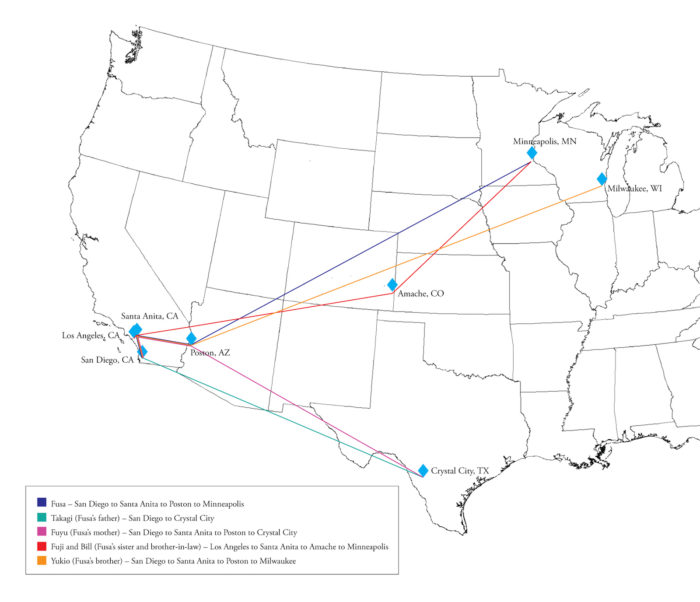

Tsumagari family migration map

Click to open full-size image in new tab.Japanese American families experienced a great deal of migration and displacement during this period. Many families such as Fusa’s were split up with individual family members going to different places for various reasons. This map shows some of the places that the Tsumagari family members lived before, during, and after World War II.

- San Diego, California: This is where Fusa and her family lived before the war. It is also where Miss Breed lived.

- Los Angeles, California: This is where Fusa’s sister and brother-in-law, Fuji and Bill, were living before the war.

- Crystal City, Texas: Fusa’s father, Takagi, was sent to a Department of Justice camp here in 1942; her mother, Fuyu, joined him upon leaving Poston in April 1944. Fusa also went here with her mother before going to Minneapolis.

- Santa Anita, California: The Tsumagari family was sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Camp in April 1942.

- Poston, Arizona: Fusa, along with her mother and her brother, Yukio, were sent to a concentration camp here in August 1942.

- Amache, Colorado: Fuji and Bill were sent to the concentration camp here in September 1942.

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Yukio left Poston in January 1943 to attend college here at Marquette University. Japanese American college students weren’t able to study on the West Coast, but they could attend school if they could find a college to accept them in a state that wasn’t on the coast.

- Minneapolis, Minnesota: After leaving Amache, Fuji and Bill went here in April and May of 1943 to work. Fusa joined them after leaving Poston in April 1944 and found a job as a typist at a department store.

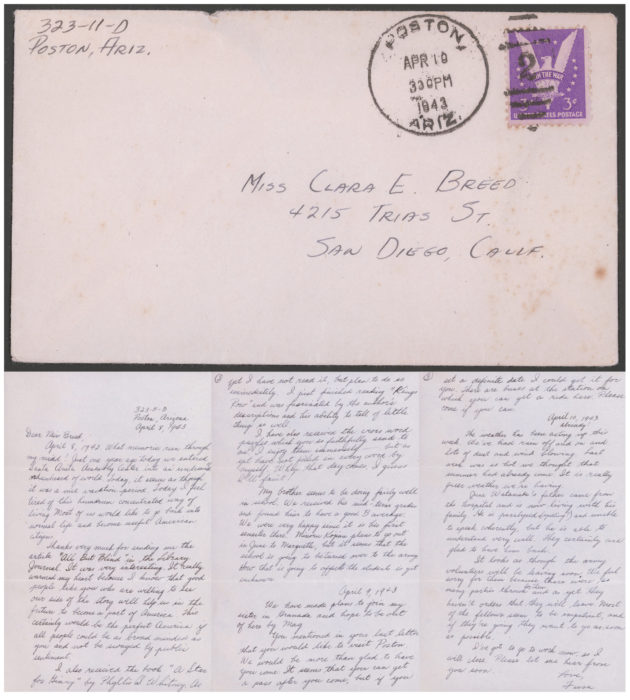

Clara Breed Collection, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Elizabeth Y. Yamada (93.75.31S)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.This is an excerpt from another letter Fusa wrote to Miss Breed. Miss Breed was the children’s librarian at San Diego Public Library from 1929 to 1945. When her young Japanese American patrons were forced into concentration camps with their families in 1942, Miss Breed became their reliable correspondent, sending them books and assisting with requests for supplies. Through her actions, she served as a reminder of the possibility of decency and justice in a troubled world.

When Fusa wrote this letter, she had already left camp in Poston, Arizona, and moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where her sister and brother-in-law were living.

- How would you describe the tone of this letter excerpt?

Even without reading the letters Miss Breed wrote to her students, one can find many things revealed in letters the students wrote to her.

- Based on the content of this letter, what can you conclude about Miss Breed?

- What evidence brings you to those conclusions?

Clara Breed Collection, Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Elizabeth Y. Yamada (93.75.31EW)

Click to open full-size image in new tab.It was not uncommon for Japanese Americans to take different migration paths from other family members. There were many reasons for this. In some cases, the head of household was removed first and taken away. In the Tsumagari case, Fusa’s father was first taken to a Department of Justice camp. College-aged Japanese Americans, such as Fusa’s brother Yukio, could go to schools farther inland, away from the coast if they could find a school willing to accept them. Since Fusa’s sister Fuji and brother-in-law Bill lived in Los Angeles, they were sent to a different camp from Fusa, who was living in San Diego. The concentration camp to which individuals were sent was most often determined by their residence at the time of incarceration. After being released from camp, securing a job often determined where an individual resettled. Work is what drew Fusa to take a different path from her mother after leaving Poston and join Fuji and Bill, who were working in Minneapolis.